Back to selection

Back to selection

Lady Vengeance

by Farihah Zaman

Lady Vengeance: Rewatching (and Saying Goodbye to) Harry Potter

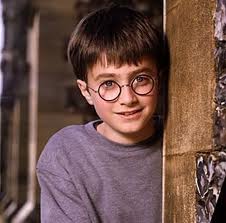

For the last ten days, the conclusion to the massively popular Harry Potter series has been jerking tears and dredging up boatloads of cash, and it seems its total box office domination is far from over. In honor of this momentous occasion I decided to undertake the unoriginal but ambitious quest of watching all of the previous films in the week leading up to the premiere. The Potter-palooza culminated in a midnight screening of The Deathly Hallows Part 2 in a strip mall multiplex near the rural Michigan town where I was vacationing, complete with buttered popcorn, limited edition 3-D Potter glasses and teenagers wearing pointy hats and apropos-of-nothing purple wigs.

The experience of looking back was not as straight-up pleasurable as I expected. The first two films, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, were available on demand in director’s cut form only, meaning over five hours of being condescended to by Chris Columbus, no easy thing to endure even with the aid of marathon-kickoff champagne. While these stories were intended for younger children and thus understandably simpler and less scary, there is no excuse for the ungodly pacing of both films. Columbus seemed to think it was necessary to take as much time as possible to convey ANYTHING; every emotion, every reaction shot, every cutaway felt excruciatingly long. While the director deserves credit for casting the wee little Britons that carried the film adaptations for the next ten years, and bringing some of Rowling’s most charming creations — the sorting hat, the Great Hall of Hogwarts, Bertie Bott’s Every Flavour Beans – to life with much more limited technology than what is available today, his two contributions to the pantheon are roundly, exhaustingly tedious.

When Alfonso Cuarón took over the reins and put his decidedly darker spin on the series in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, fans everywhere rejoiced, and many still consider it their favorite film, perhaps partly out of the memory of deep relief. The film still has some awkward storytelling moments – the length of the books means many of the films can feel at times like visual Cliff’s Notes or companion pieces for them, and this installment hinges on an always-tricky-to-incorporate bit of time travel – but the injection of style, mood, and decent shot composition remained invigorating. By comparison, the Mike Newell directed Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire felt like a bit of a step backwards after the novelty of a more distinctive directorial voice that Cuarón initially brought to the table had worn off. I remember being terribly excited to see it when it came out, not least of all because of the Jarvis Cocker cameo, but the mere suggestion of watching Goblet of Fire elicited groans from my Comrades-in-Potter, and it seems to pack in too much plot for not enough payoff. Also, while the discovery of an international wizarding community was as exciting a revelation for readers and viewers as it was for Harry, the ethnic and gender stereotypes were annoyingly, close-mindedly familiar, especially considering one of the major themes of the series is tolerance for those of different birth.

What brought the most lucrative series of the modern world into the hands of short film, TV movie and mini-series director David Yates remains a bit of a mystery, but his work in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix was obviously worthy enough to keep him on through the next three films. This felt like the most rushed movie of the bunch, but like many I appreciate its deft turn into overt politics, and the return to the more stylized aesthetic of Prisoner of Azkaban. Montages of Dumbledore’s Army gaining skill and confidence in the room of requirement give off a believable, revolution-movie feel by referencing real world bureaucracy and modern filmmaking shorthand. Furthermore, while all of the pedigreed adult actors in the series are well cast if sometimes under-utilized, Imelda Staunton as the Roald Dahl-ishly named Dolores Umbridge, one of the books’ first and best reminders that evil is not always easy to detect, was particularly brilliant. The sixth film, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, is among the most exciting, but also makes some of the worst omissions. Unlike the fifth film which cuts just enough from the book to come together into a coherent, standalone film, Half-Blood Prince drops the exploration of Harry and Voldemort’s previously mentioned psychic link, as well as the entire story of Harry discovering via Snape’s memories that his father was not the perfect hero, and Snape is not just a perfect villain. Yates somewhat makes up for the omission by including it in the final film in truncated form, but a quick flashback in the heat of battle is not the same as watching Harry slowly and painfully come to understand that people can be complicated, and accept the truth about some of the most mysterious adults in his life.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1, despite its occasionally clumsy construction, is my favorite of the series. The directorial voice is strong, there is minimal exposition, and the young actors have come into their own. Yates makes some unexpected aesthetic choices, such as the shadow puppet animation in telling the wizarding folktale of The Deathly Hallows. The threat of danger is for the first time immediate and oppressively pervasive. There is a quality of quietude and skilled patience in its exploration of the frustration, the torment, of waiting, that makes it markedly different from the other films. Deathly Hallows Part 2, cathartic and satisfying in many ways, is still its flawed counterpoint, the messy, inevitable storm after the quiet.

Although it was not all fun and games, I’m glad I soldiered through the bloated but ultimately entertaining Potter-verse in its entirety. Watching the characters grow up over the course of several hours, from the tiny, mewling kiddies of Sorcerer’s Stone to the lanky, handsome teenagers of Deathly Hallows is strange and satisfying, as is being able to rehash the relative merits of the two men who played Dumbledore (Richard Harris never conveyed the darker side of the great wizard’s power, but perhaps he would have as the series matured, while the almost brusque Michael Gambon never quite got the loopy side of Dumbledore’s personality, but might have under different direction). The series also serves as a kind of compendium of CGI and other film technology in the last decade, as their consistently enormous budgets meant each film represented the best visuals that money could buy at that time, from the video-game looking Quidditch matches and late ’90s Home Alone aesthetic of 2001 to house elves that actually look solid and eerily humanoid ten years later.

Although it was not all fun and games, I’m glad I soldiered through the bloated but ultimately entertaining Potter-verse in its entirety. Watching the characters grow up over the course of several hours, from the tiny, mewling kiddies of Sorcerer’s Stone to the lanky, handsome teenagers of Deathly Hallows is strange and satisfying, as is being able to rehash the relative merits of the two men who played Dumbledore (Richard Harris never conveyed the darker side of the great wizard’s power, but perhaps he would have as the series matured, while the almost brusque Michael Gambon never quite got the loopy side of Dumbledore’s personality, but might have under different direction). The series also serves as a kind of compendium of CGI and other film technology in the last decade, as their consistently enormous budgets meant each film represented the best visuals that money could buy at that time, from the video-game looking Quidditch matches and late ’90s Home Alone aesthetic of 2001 to house elves that actually look solid and eerily humanoid ten years later.

There are deeper rewards for re-watching the entire series as well. J.K. Rowling’s primary strength as an author is narrative rather than stylistic; she’s most impressive in making connections between more recent and seemingly long-dormant plot points. This means the viewer will definitely benefit from, not to mention enjoy, a detail-oriented review. Remember how Harry used a basilisk fang to kill Ginny’s possessed diary? How the Marauder’s Map had several collapsed secret passageways? How Snape was actually one of Lily Potter’s first friends as a child? I didn’t, until I sat down for nearly 20 hours of green screen “magic,” burgeoning hormones, and dueling wands. Themes also connect more clearly across the series in the compressed timeframe, from the idea of good and evil having a more porous boundary than Harry initially imagined, to resisting the persecution of minority races, to, most importantly, death and the acceptance of mortality. The series repeatedly comes back to the idea that while we may fight mortality, inwardly in the case of muggles and more actively in the case of wizards and witches, death is essential to the concept of being human (Voldemort’s humanity is shattered by his unnatural, unending quest for immortality). I had forgotten that this premise was stated simply in the very first installment with the story of Nicolas Flemel and the Sorcerer’s Stone, lo those many hours of reading or viewing ago. Upon hearing that Flemel will die after his stone is destroyed, a wide-eyed Harry is distraught, and Dumbledore tells him “To the well-organized mind, death is but the next great adventure.”

Farewell, Harry Potter.

FARIHAH ZAMAN began working in film as a Programmer for Film South Asia documentary film festival before moving to New York in 2005, where she was the Acquisitions Manager at independent film distribution company Magnolia Pictures. In 2008 she coordinated IFP’s No Borders program, the only international co-production market in the US, before becoming Program Manager of The Flaherty Seminar until 2010. Farihah currently writes for The Huffington Post, as well as online film journal Reverse Shot, among others.