DESIGNED FOR LIVING

With his wild and joyful new film, Gregg Araki, indie-America’s foremost chronicler of teen angst, steps gleefully into the realm of romantic comedy with a picture that owes more to Hawks than Godard. Peter Bowen talks to Araki about his embrace of sunnier emotional climes in Splendor.

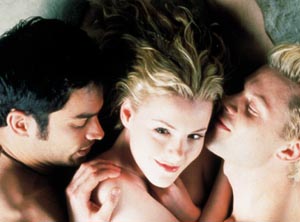

Left to Right: Jonathan Schaech, Kathleen Robertson, and Matt Keeslar in Gregg Araki's Splendor

For the last decade, Gregg Araki’s films have marked the unexpected twists and turns of American Independent film. His first features, Three Bewildered People in the Night and The Long Weekend (O’Despair), were blueprints for no-budget filmmaking. Shot as guerrilla films and tossing off cinematic references and conventional morality, the pics were home movies of another L.A. Made for only $5,000, Three Bewildered People went on to win the Bronze Leopard, Young Cinema Award at Locarno. His 1992, The Living End spearheaded what would be quickly dubbed the "New Queer Cinema" at Sundance that year. But just as this boys-with-HIV-on-the-run romance paved the way for Hollywood’s Philadelphia, its flip, ironic and decidedly politically incorrect tone angered many within the gay community.

Marrying Godardian cinematic style with industrial music, Araki then went on to capture the gothic zeitgeist of the ’90s with his teen-angst trilogy. Totally F***ed Up, his most ardent homage to Godard, uses a fragmented narrative of video interviews and broken hearts to illustrate the fragment psyche of modern teens. In The Doom Generation and Nowhere, Araki veers off towards heterosexuality, violence and a new and dense expressionistic film style. While some branded the films nihilistic and surreal, recent high schools have demonstrate much too tragically how accurate Araki’s vision was.

With Splendor, Araki takes another radical turn. Harking back to ’30s screwball comedy, Splendor spins out a giddy romance in the form of a menage-à-trois between a smart soulful Abel (Jonathan Schaech), a blond hunk Zed (Matt Keeslar) and Veronica (Kathleen Robertson) who, unable to choose, takes them both. While Splendor expands Araki’s acerbic interrogation of L.A.’s tarnished values, the film also luxuriates in that town’s glamour and eternal optimism. Indeed the great joke of Splendor seems to be that the industry that swallows everyone has been thoroughly digested by Araki in this revision of classic Hollywood comedy. Splendor is due out this Fall.

Filmmaker: Early on you were often dubbed an American-indie Godard, but Splendor seems to be indebted to Truffaut.

Gregg Araki: Another magazine said that this is my Woman Is A Woman, a shockingly upbeat movie after a string of dark films.

Filmmaker: The film’s brightness is certainly a detour from your teen-angst films. How does this film fit into your work so far?

Araki: There is for me an aesthetic thread. But more importantly there is a connection with my other films in that there is a romantic core to the work. It has been part of my films since 1989 – a romanticism bordering on the naive.

Filmmaker: Is American independent cinema becoming happier?

Araki: Quite the opposite. I feel that independent film, like Happiness, tends to be much more nihilistic. With this whole millennium thing and the start of a new century, there is the hope of moving forward, I suppose. A certain part of this, at least in my case, comes from a certain sense of maturity and coming of age. The difference between this movie and The Doom Generation has to do with the musical soul of the movie. Doom Generation is a very Nine Inch Nails type of movie, very angry. This movie has more the sensibility of where I am now, which is much more a groovy, ecstasy, peaceful type of movie.

Araki: Quite the opposite. I feel that independent film, like Happiness, tends to be much more nihilistic. With this whole millennium thing and the start of a new century, there is the hope of moving forward, I suppose. A certain part of this, at least in my case, comes from a certain sense of maturity and coming of age. The difference between this movie and The Doom Generation has to do with the musical soul of the movie. Doom Generation is a very Nine Inch Nails type of movie, very angry. This movie has more the sensibility of where I am now, which is much more a groovy, ecstasy, peaceful type of movie.

Filmmaker: Was it clear to you when you wrote the film that you wanted it to end on a beginning?

Araki: Most of the time I don’t really know where a film is going to end. With certain films, I begin with an ending. With Totally F***ed Up I knew where the film was leading. But with The Doom Generation, I knew something was going to happen, but I didn’t know what. With Splendor, it was not so clear where it was going to end up. I knew that I wanted a sort of Design for Living-type situation. I knew it was going to end on an optimistic note, but what that was I didn’t know. I did know that this was going to be my first movie with a happy ending.

Filmmaker: In your earlier films, historical conditions usually pre-determine a less-than-happy ending. In The Living End, there was the AIDS epidemic, and in the teen films a sense of conservative backlash. In this film, such historical and political realities don’t shut down the possibility of a happy ending.

Araki: There is an optimistic mental space. The films between The Living End and Nowhere have been misinterpreted as nihilistic. While those films don’t end on such a happy note as Splendor does, they all end with a sense of uncertainty, which isn’t necessarily nihilistic. They are just unsure.

Filmmaker: Do you find that people consider happy films to be lightweight?

Araki: There is a sort of prejudice, or misrepresentation, that because a film is optimistic or a romantic comedy or whatever, that it lacks certain seriousness. I think that’s a very superficial read. For me, movies like Bringing up Baby are incredibly profound and provocative – more interesting than Citizen Kane. There is such a deconstruction of manners and social structure. People have dismissed things that appear to them light and light-hearted; they are trained to look at Saving Private Ryan as a deeply moving film, because it is not light. For me it is incredible that Sturges could pull it off. Certainly in retrospect, Sturges and Hawks and others get their due through critical analysis and attention. But generally I find these films deeply profound and moving in a light-hearted way. I find them more complex – all these fascinating things are going on, but they are being worked out, or excused, within this conventional drama.

Filmmaker: How did you come to make a screwball comedy?

Araki: Partially this movie grew out of doing the teen-angst films and getting flack for only doing teen-angst films. People would say, "Can’t you do anything but teen-angst films?" And I would always have to explain that it was a trilogy. There are three films to a trilogy." After that I wanted to do something different, and from film school my two favorite genres were the screwball comedy and the couple-on-the run film. I was supposed to do a studio film at New Line about two years ago. But the movie didn’t happen. As an antidote I started working on a smaller project that was a screwball comedy. I wrote to Kathleen, Matt and John with the idea of the three of them together. The very concept was reliant on the idea of movie stars.

Filmmaker: Threeways seem to be a common denominator in your films.

Araki: Yes, I guess. There’s Three Bewildered People in the Night. Then there are six people in The Long Weekend, I guess it has to do with the polymorphous sexuality that is interesting to me. I guess that is why, opposed to the nuclear couple, there is always some other element thrown in.

Filmmaker: It strikes me that even though you have been labeled a gay filmmaker, your use of triangles suggest you’re more interested in narrative perversity.

Araki: I didn’t really start with gay characters. They were more polymorphous and sexually confused. And then The Living End and Totally F***ed Up had my most gay characters. But even there the couple thing is a problem; there isn’t much one can do with it. Boy meets Girl, or Boy meets Boy, and that is all there is – in every single movie. The Romance. In the threeway there is confusion and the element of unpredictability. The dynamic is much more interesting because it is just not a part of what we perceive as Western civilization. I think that is what Splendor is ultimately about. – about being outside of that pairing.

Filmmaker: When you were writing Splendor, did you do any research into actual three-way marriages?

Araki: Normally in my films I don’t go there. The film comes from me putting myself in their place, thinking about the kind of emotional ramifications of their situation. There is a chemistry between the three of them that cannot be divided into two. It is part of the way that Abel and Zed are yin and yang. Together they complement each other in a way that makes sense. The film doesn’t really focus on the homoerotic elements, except when they are forced to kiss and it becomes somewhat tantalizing – which is a kind of reversal of the usual two lesbians kissing for a guy. But there is chemistry between the Abel and Zed characters. It is about how they work that out, together and each alone. Together there are a sort of rules, which they need to figure out. And to some extent that is what the film is about – figuring out how they are going to live.

Filmmaker: That element of having to figure things out – whether you’re queer, perverse, or a pissed-off teen – is a consistent element in your work.

Araki: The film is very much about trying to live by your own rules. Which is probably why in certain boring circles, it’s controversial. It’s not trying to tow any one line. Some of my angrier and anarchical early films are about stuff getting destroyed. This film is more about re-building and finding an alternative structure.

Filmmaker: Screwball comedy seems to making a comeback these days, even with many gay films.

Araki: I just saw that Sandra Bullock film, Forces of Nature, which was clearly a Bringing Up Baby knock-off. The screwball comedy is all about repression and not having sex. In my movie they have sex, but they also have codes and conventions that are taken from the genre. My desire was to remake screwball/Lubitcshen comedy, but then to also revise it so as not to fall into the trap that so many of these films, like What’s Up Doc? or Forces of Nature, fall into. Because those remakes are not of the period, they cannot capture the élan of those movies. Real screwball comedy definitely came out of a specific social and economic context.

Filmmaker: The other thing about Splendor is how it messes with the classical construction of comedy. Typically comedies, even screwball comedies, end in marriage, signifying that social and political harmony has been restored. But with a three-way you get to have your marriage and eat it too. The order restored is fundamentally unconventional.

Araki: That’s exactly it. The movie is very much about achieving conventional happiness in an unconventional way.

Filmmaker: Your films use a fairly defined visual vocabulary. How do you construct a happy film?

Araki: We were going for a specific aesthetic. I wanted to make the most gorgeous film ever made. I wanted the colors to just trip off the screen. I wanted the film to have that early ’40s movie-star glamour, as well as a New Millennium, post modern, new wave feel. The old and the new together. Trying to envision the future by looking backwards. I set it two years in the future which is not long enough to be futuristic, but long enough to feel new.

Filmmaker: Where does the title come from? Is it supposed to evoke the Wordsworth line of "Splendor in the Grass?"

Araki: No, it was a rave music sort of vibe. Especially that big Everything But The Girl song ["Before Today"] in the middle of the movie. It is electronica, but tending towards its warm end rather than its hard techno side. I think of it more like the film Splendor in the Grass. Or as one of Matt’s friend calls it "Splendour in the Ass." But I picked the title because it is such a gorgeous word.

Filmmaker: You have worked with Kathleen Robertson (Veronica) in Nowhere and Jonathan Schaech (Abel) in The Doom Generation. In the earlier films their characters were much more edgy and dangerous. Here the characters are cute; there’s nothing particularly ferocious about their sexuality. Was that a certain acting style you were after?

Araki: There was a stylization to the action, especially in the final act, a sort of groovy style with slapstick. On the one hand, I wanted the acting to be naturalistic and human. On the hand, I wanted a sort of Cary Grant stylization. As in screwball comedy, the emotions are real, but there is also a kind of sheen to the performance.

Filmmaker: What other genres would you want to do? Or which ones do you hate?

Araki: I’ll never do a gangster film. That genre is so completely dead and over – Guy shooting at each other and yelling "fuck you!" What can you do to that? I would love to do a musical. I would also love to do an action movie – a $50-million action film, like my favorite film last year, Face Off.

Filmmaker: You seem very aware of film history and film language. Recently, there is a sense that independent filmmakers do not see themselves indebted to any kind of film history.

Araki: I find that so sad and so myopic. When I was on the jury at Sundance two years ago so many films didn’t have a sense of film history or film language. There is a rhetoric – I just want to be a director. So their film just becomes a bad statement about how badly they want to be a director. There are no references in terms of the flow of film history. Personally I think it hurts their work and is super limiting. But it is also bad on the other side, to be slavishly devoted to a filmmaker, like Scorsese, or whoever.

Filmmaker: In a way this claim to be free of genre is creating a whole new genre – the Independent film.

Araki: I don’t think so. That’s the thing about film language. It has been around for 100 years. All films have been done, even experimental films.

Filmmaker: Here is the Stan Brakhage scratched film, the homoerotic Kenneth Anger film, and so on?

Araki: That is why the interesting filmmakers working today really know about film. They have seen everything. Like Rick Linklater or Todd Haynes. They are really walking encyclopedias. They have seen every obscure movie ever made. And it shows in their movies. They know what the language is and know how to use it. Otherwise, it is like trying to be a writer without having ever read a book.

Araki: You come in using that language, knowing how to speak it to make your own statement. For example, The Quik-E mart scene in The Doom Generation comes straight out of Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin. But no one is going to say Eisenstein directed that. It’s related in that I have seen the scene so many times that when it comes to doing the storyboards, that scene comes out, but filtered through my sensibility.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →