THE DISEASED WORLD

With 28 Days Later, Trainspotting director Danny Boyle re-invents the apocalypse movie while evoking an all too plausible vision of a virus-ravaged London. Horror critic Kim Newman talks with Boyle and screenwriter Alex Garland about genre moviemaking, DV, and the British dystopian tradition.

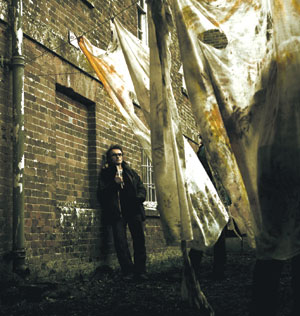

28 Days Later director Danny Boyle. Photos: Peter Mountain.

Anti-vivisection activists make a very bad judgment call and uncage an experimental monkey infected with "rage." Twenty-eight days later as the title has it, bicycle messenger Jim (Cillian Murphy) wakes up from a post—traffic accident coma in a deserted London hospital and ventures out to find the quarantined city depopulated and the few remaining normal people doing everything to avoid the jittery, savage, zombie-like "infecteds" who attack on sight. Our bewildered hero hooks up with several others – including a tough black woman (Naomie Harris) and a likeable London cabbie (Brendan Gleeson) – on a perilous trip northward, to seek refuge at an army officer’s (Christopher Eccleston) fortified retreat. However, even if they survive the plague, the future of humanity is in doubt.

Having established a reputation with such low-budget, high-energy British films as Shallow Grave and Trainspotting and then become somewhat adrift in more international waters with A Life Less Ordinary and The Beach, director Danny Boyle here returns to his roots with a lively genre picture that manages at once to be both a small-scale character piece and a post-apocalypse epic. Scripted by novelist Alex Garland, author of The Beach, this is a terrific s-f/horror hybrid, evoking American and Italian zombie movies but also a very British end-of-the-world tradition that takes in War of the Worlds, The Day of the Triffids and Doctor Who. Shot on digital video by Dogme specialist Anthony Dod Mantle, who gives the devastated cityscapes security-cam-look realism, 28 Days Later grips from the first, with its understandably extreme performances, its terrifyingly swift monster attacks and its underlying melancholy. A box office success in England, it may just be the best British science-fiction/horror film since Death Line in 1972.

|  |  |

| Stills from 28 Days Later, starring Cillian Murphy and Naomie Harris. | ||

Filmmaker: So, 28 Days Later, why make it?

Danny Boyle: Its amazing premise. A virus outbreak at the beginning of a movie is not original, really. But this had an original twist, which is that it’s a psychological virus. Then it was followed by this deserted, abandoned London. I knew I was going to do the film as soon as I got past page five. You die for those kinds of ingredients.

Filmmaker: Alex, did you just sit down one day and think, I’ve got an idea for a science fiction movie?

Alex Garland: Yeah. Initially it was just an on-spec first draft script. And I showed it to Danny at an incredibly early stage.

Filmmaker: Because you’d worked together before?

Garland: Not really. I’d watched him making The Beach, but I hadn’t been working with him. I wanted to get involved in films, and I went out to see them shooting in Thailand with an agenda – to learn as much as possible.

Filmmaker: And did you feel "I can do that"?

Garland: Yeah, it was a piece of cake! "Oh, any cunt can do this!"

Filmmaker: What were your original inspirations for the story?

Garland: Most British schoolboys have read [John Wyndham’s] The Day of the Triffids, and also I’m a huge J.G. Ballard fan. He wrote three novels set after an apocalypse, each with a different premise: no water, lots of water, the world setting into crystal. And I loved those novels, I loved the atmosphere. And also the films of George Romero. There are references in the film, and people familiar with those things will pick up on them very quickly. There was one other thing, just so it doesn’t sound like it was purely ripping off other people. Partly – and Danny and I worked closely on this – it was just a paranoid story coming out of the paranoid time. Lots of stuff was happening in this country that felt like the right kind of social subtext or social commentary that you could put in a science fiction film. Danny was particularly interested in issues that had to do with social rage – the increase of rage in our society, road rage and other things. Also our government’s inability to deal with things like BSE [mad cow disease], Foot and Mouth. You always felt that if a virus exploded into our country, our government would be 20 steps behind wherever the virus was.

Filmmaker: The film has obviously worked for audiences who are too young to know the things you are drawing upon.

Garland: Yeah, because they all think it’s ripping off Resident Evil... which irritates me to no end! You could say, "Look, he’s ripped that off Day of the Triffids, and that off of Dawn of the Dead," and I accept that and say, "Sure I did." But it’s not Resident Evil!

Filmmaker: And so how did you do this on what I’m assuming is not an enormous budget to make, frankly, a huge-scale action-type picture?

|

| Cillian Murphy in 28 Days Later. |

Boyle: That was one of the biggest factors in making the film. Normally making a sci-film [requires] a huge budget, but we wanted to keep the budget down to about �6 million, and we did that because we didn’t want any stars in it. We wanted it to be just ordinary people. Not having the money can be a problem or it can be a kind of freedom, and for us it was a freedom. We couldn’t do deserted London in a realistic way because after a catastrophe like this, there’d be burnt-up cars, there’d be bodies everywhere, and we could only just get permission to stop traffic for just a couple of minutes at a time. And, we didn’t have the time or the money to dress [the London streets]. So that leads you towards coming up with something better, and we came up with this idea of "just stillness." That was something we were really pleased with in the end, because it’s quite difficult without a budget to make a really cinematic film about London. And the images at the beginning of the film are a fantastic calling card. Even people who don’t like zombie films or monster films are still intrigued by these images of London, which is a city everybody knows is packed, hectic, crowded.

Filmmaker: You still got a couple of "money" shots. Did you find that shooting digital video made getting these easier?

Boyle: Definitely. Covering that [petrol explosion] on film would have been much more expensive, but we had all these really cheap cameras and a brilliant cameraman [Anthony Dod Mantle] who is the world’s leading expert on DV. I remember thinking that the petrol explosion, when it goes off at that station, it’s got to be on a level with all the mainstream action movies. Otherwise you get that terrible thing that you get sometimes with British films where there are events that are a bit disappointing when you look at them on the screen – they show their budgets a bit.

Filmmaker: You seem to have sidestepped that by showing that kind of stuff in a different way. Some sections of the film are much more effective because they look real, like the footage we’ve seen from Northern Ireland all our lives.

Garland: What you may have picked up on is that we deliberately referenced images from news footage throughout the film. So the church is from a photograph of Rwanda, and there was a shot in the petrol station that’s from a bomb going off in Northern Ireland. And when they’re being led out to the execution ground, that was referenced from a photograph from Bosnia.

Boyle: There’s one point when [the protagonist] picks up all the money on the steps outside Buckingham Palace, and that’s from a very famous photograph taken after the Khmer Rouge abandoned Phnom Penh. The streets of this deserted city were literally covered in money.

Filmmaker: Danny, I have noticed that most of your films seem to have a structure where the first half is episodic and mosaic-like, and the second half is much more plot-driven. It’s almost like "episode two" kicks in midway through and then you have a claustrophobic bunch of characters stuck together doing something. Is that a conscious choice or just the way your mind works?

Boyle: That’s partly a budget thing. If you have limited money, you can use what resources you have occasionally, while most of the time, you create your film with a small group of people. [This approach] is also a fascinating way of looking at anything, really – through an interior world of people. Like Shallow Grave – we made the "landscape" of the film, which you normally associate with exterior shots or expanse, the interior of a flat. You use tricks like that to make your film cinematic but with limited resources.

Filmmaker: Did you rewrite as you were shooting, or did you lock the script before?

Garland: It was never locked! I showed the script to Danny immediately, so we were working on it together right from the beginning. There was something like 50 sets of revisions before we started shooting. Then during filming, we were changing all sorts of things. The film got more paranoid as it went on. Sometimes Danny would call up and say, "Quick, come in, I think we’re going to change this." And we’d figure out how to do it.

Filmmaker: In generic splitting-hairs terms, did you see it as more of a zombie movie or an apocalypse movie?

Garland: Apocalypse.

Boyle: Yeah. We were very worried about people thinking it was a zombie movie, because I think if you’re a zombie fan, you’ll be disappointed. I thought of it as a science fiction film that happens next Wednesday, which–

Filmmaker: It can’t be because Tony Blair is still prime minister.

Go to sidebar: Apocalypse Fiction Redux

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →