SUNDANCE FEATURES  Thursday, January 28, 2010

DADDY LONGLEGS' JOSH AND BENNY SAFDIE |

By Scott Macaulay

When I was asked by The Huffington Post to comment on New York movies premiering in Sundance, the first film that popped into my mind was Josh and Bennie Safdie's Daddy Longlegs. Now, as you may know, I'm a big fan of the Safdie brothers, selecting Josh for our 25 New Faces for the film he directed, The Pleasure of Being Robbed in 2008. That picture is a delightfully freewheeling romance of sorts involving a young woman, played with depth and originality by Eleonore Hendricks, who casually steals, not out of maliciousness or for greed but simply because of a worldview that sees the world as hers. This second film, Daddy Longlegs, directed with his brother Bennie, extends the Safdies' emotional range further. It's the story of Lenny, a projectionist and divorced dad, and it's set during the summertime two weeks he has custody of his two young sons. Lenny's lifestyle is both perpetually frazzled and compulsively bohemian, and his take on parenthood is somewhere between unaffected love and a call to child services. Lenny is based on the Safdies' own dad, and their ability to weave their complicated emotions about him into a work that is alternately shocking, free-spirited and joyful is testament to their extraordinary emotional intelligence as directors. Much credit goes to Frownland director Ronnie Bronstein, who plays Lenny in his acting debut. There's some of Bronstein's naturally searching loquaciousness in Lenny, but there's also the keen intelligence of an actor firmly aware of the implications of his choices. Daddy Longlegs (previously titled Go Get Some Rosemary when it world premiered at the Cannes Film Festival's Director's Fortnight) screens tonight, January 28, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music as part of Sundance USA. Whereas other films from the festival are headed out to cities around the country, Sundance has appropriately sent the Safdies back to their hometown. Kids and irresponsible dads exist everywhere, but there's a particularly Gotham flavor to the brothers' filmmaking, a capturing of the people and textures of this city that will thrill all of its cineastes. If you miss tonight's screening, you can catch the movie on VOD through Sundance Selects for a limited time before its theatrical launch later this year. Filmmaker: Let’s start by talking about how you wound up casting Ronnie Bronstein, the director of Frownland, as a character based on your dad. Josh Safdie: It started with registration at SXSW. I didn’t know he was a filmmaker. I genuinely thought he was a lost silent film actor, like a celebrity from the 1920s. I was totally intimidated by him. The night he won the [Special Jury] award, the programmer who selected both our short, We’re Going to the Zoo, and Frownland, came up to me and said I should meet him. I missed Frownland because I had left my key in the car running overnight. I had this crazy experience — the windshield wipers rubberized my windshield because it was running all night and it was raining. When I was introduced to Ronnie, I said, “Something must be important about you because when I was trying to make your screening I left my keys in my car overnight….” He was weirded out by that introduction, but he and [d.p.] Sean Williams still went to see our short the next day, and they liked it. Benny: I had been trying to make a short, and that night Josh sent me a photo that had Ronnie in the background. He said, “This guy has got to be in something. Email him about the short you want to make.” So, I sent him this really formal email out of the blue, which to this day, every month, he’ll send back to me. There’s something really weird about seeing yourself so distant from someone you are now really close to. Filmmaker: What happened next? Josh: Ronnie was showing Models, the Frederick Wiseman movie, at AMMI, and invited us. I loved the film, and that’s when I asked him, “This is going to seem very weird, and I know my brother contacted you about playing this silent comedy actor, but I think you’d be really great in this story I wrote with my brother. It’s about a dad.” Benny: [His casting] was a confluence of things. One time he was showing Frownland in Boston and had nowhere to stay. He gets my number, calls me and says, “Can I stay in your place in Boston?” I was like, okay, but we didn’t really know each other, and suddenly we’re staying in the same apartment. We watched Reflections of Evil and then walked all over Boston together. That’s how we got to know each other. Filmmaker: So how did you merge what you discovered in Ronnie with your vision of your dad? Josh: I remembered Ronnie’s demeanor based on the speech he gave at SXSW [when he won the award]. He said something like, “This is not a careerist opportunity for me” — there was something goofy to it. Then I saw Frownland a bunch of times, and then we hung out with him. We worked together on [Mary Bronstein’s film] Yeast. We got to see both his ugly side and his slapstick side – he’s a really silly guy. We knew the character we were writing wasn’t Ronnie, and we knew that he didn’t want to play himself, so we came up with this character Lenny, and that’s when the movie took its second form. [Ronnie, Bennie and I] sat down in a diner, three days in a row, eight-hour sessions, and we talked about the movie so much that he knew it. We had written Go Get Some Rosemary as a 44-page story but, in fact, he never read it until after we were done shooting. It was in that diner that the real casting [took place]. We knew exactly what he was capable of and not capable of. Benny: All just from the looks on his face. If we told him about a scene and it didn’t hit anything with him, we realized that scene wasn’t going to work. We had to tailor this weird version of our father into Ronnie. Filmmaker: But what was it specifically about Ronnie that prompted you to think of him as a character based on your dad? Josh: I think it’s the silliness mixed at the same time with the seriousness. We see our dad in that. When I think of our dad, I think of this lonely guy who was delivering jewelry in midtown in the late ‘70s, and I could really see Ronnie [playing that kind of character]. The big difference is that our dad was not an American. He fancied himself as an American, but he became an American in 1982. English is his fourth language. Benny: He is not as verbose as [Lenny]. Filmmaker: Tell me about the balance between comedy and critique in the film, about constructing the complicated nature of Lenny’s character. Josh: The movie is a weird meditation on perspectives. It’s very much from the perspective of the kids, but at the same time it’s from the perspective of this man. Ronnie was kind of our soldier in the field — he was our tool to express ourselves as we are as adults. I’m very grateful to him for that. That’s where the movie started to become more complicated, when we realized that he had become a very good, contemporary friend of ours, and we were going to express ourselves through him. That’s where the complicated perspective of the movie comes from — in that initial sit down we realized that his [character] wasn’t just a father figure, it was also us. Filmmaker: What about the process of directing him on set? What was that like? Josh: Ronnie in the preproduction process was very cerebral about it, and in the production he became very emotional. Benny: There were certain times we would sit down with a scene, and he’d come at it one way, in one frame of mind, but [Josh and I] would have sat down the night before, reconciled our differences, and put together a unified vision. And we would know, “Ronnie is really going to pull [the scene] this way, and we have to do something that throws him off it in the opposite direction!” Josh: It was like chess. Ronnie loved that aspect of it. Benny: And even while we were filming, Ronnie would know that I’d be more open to certain things than Josh — Josh: So he’d go to him for those things! Benny: It was almost like a war, or a battle, but we always knew it wasn’t an ego thing. It was always about ideas. Josh: That’s why [Ronnie’s] was the biggest casting decision. A really good actor will question the ideas of a scene and the validity of its emotions. Filmmaker: Did the filmmaking process change for you on this second film? Josh: Absolutely. The first movie was — Benny: — way more organic. Josh: I have a lot of respect for that movie because it was very much like a jazz improvisation. We knew the melodies, and then we kind of went into our own solos. I’m very respectful of that, and I think it’s a triumph, personally, but we had no idea what we were getting into when we started. I had a lot of mangled, gutteral feelings when I thought of Eleonore as her character, who turns out to have been very much a character. I’ve been with her now two and half years, and it’s weird, we did this interview for French television and they shot it on the Staten Island ferry, and she popped this question: “Do you ever think we could work together again like we worked together on Pleasure of Being Robbed?” And I said, “No, I don’t think so.” We saw each other as such caricatures, and those caricatures we were able to write. Now we know each other and we know all these things about each other so the caricatures are negated. Benny: There’s less mystery. Josh: But the difference [in the making of the two films] is that we knew what we were getting into when we embarked on Daddy Longlegs. Benny: There was a beginning and a definite ending. Josh: And we knew the complications. We knew there were two direct perspectives of the movie. There was a harsh perspective, where you are super-critical of this person, and then there was also an extremely loving, compassionate perspective. And we knew we wanted them both at the same time. That’s, to me, the biggest success of the movie, that its perspective completely dances — you don’t know if you love [Lenny], you don’t know if you hate him. Benny: It’s subjective too. You can watch the movie and be veered down one path, where you just see the hate, and not even know the other loving side exists. Each subjective [position] exists separately, and that they don’t make an objective movie is strange. We wanted [the audience] to feel this weird duality of how we feel towards our dad. Josh: And how we feel towards ourselves too. Benny: Writing about somebody’s criticisms to point out the reason you love them is really difficult. Filmmaker: What was it like as brothers directing together? Josh: The most appropriate fighting happened. We would hash out our ideas even before rehearsals so we knew that if we were arguing we’d know that the only thing was wrong was not our relationship but that an idea was wrong. If we were having an argument we knew that something wasn’t right, and that was a very comforting thing to know. If we’re arguing about something, it would turn into a stupid personal fight but then we’d know that something wasn’t right in a scene or on a page. Benny: We’ve always had ourselves as constant companions, so we have similar ways of looking at things, but there is a slight difference. I’m more critical, or more analytical — Josh: And I can romanticize things. Benny: And that crunching together produces a deeper perspective than what we would have done individually. Josh: Because there’s complication. Benny: I learned so much more about him and myself. Josh: And on a technical level, I shot 50% of the movie, and Benny did 50% of the sound, so a lot of times in these intimate scenes there was me with a camera, and there was an unspoken dynamic. Benny: This seems really cheesey, but I guess it made sense that you were looking at it and I was listening to it so we had to trust each other. Josh: We were shooting really long-lens stuff, so a lot of times I couldn’t hear the dialogue. When we were shooting out in the streets, we never wanted unsuspecting strangers to look and see a film crew. We wanted them to see this guy manically running into his apartment with his two kids. We wanted them to tell their friends and have the movie live on in their dinner conversations. Filmmaker: Tell me about the editing — what the process was like, and what kind of decisions you had to make. Josh: Ronnie helped us edit, and then we shot four extra days to fill holes – logical holes, continuity holes, and emotional holes. Benny: The reshoots on this [film] were so strange. They felt like pure business. “We’re trying to go from here to here and it’s not working. We need to write a scene to fill that hole.” It was about filling these holes. Filmmaker: How were you guided? Was it just yourselves, or did you do feedback screenings? Benny: We don’t do that. It was mainly the two of us, and Brett and Ronnie sitting down watching. If something didn’t fit right, you, Josh, would say, “I don’t know what I think of this scene,” and that would start this enormous discussion. We’d go from the highs and the lows and we’d eventually cut out something we loved. Filmmaker: When was the first time you saw it with an audience? Josh: We showed it to the six-person crew, and there were two extra people in the studio at the time, so there were eight of us. It was an assembly, but we had already cut 40 minutes. We did some sound design, but emotionally it was a rough cut. That was probably the closest thing we’ve done to [a small group screening]. The biggest thing people said to us was, “That’s a monster of a movie.” It was so long! We took it as a compliment: “We deflated our audience!” But the most important feedback we got from those eight people was that there was so much emotion [in the film]. It was playing flat towards the end. Everybody said, “It has to be an hour shorter.” And that’s when the movie kind of went into a spiral. We started cutting things really randomly, totally in the moment. We had to stop, and we moved the editing to Benny’s bedroom, and then Ronnie really started becoming part of the conversation. He’d come over and we’d have these massive conversations and then we’d do an edit. Benny: Those were crazy 18-hour days. Josh: We were trying to make that Directors Fortnight deadline, which was good, because I really believe in deadlines. Filmmaker: How do you see yourselves in relation to the independent film industry right now? Where do you see yourselves as fitting in? Benny: I don’t know what it’s like on set for other films. I don’t know if it’s in any way like what we are doing. In some way it does feel like we’re a little separate, like we are at this other table. But I don’t really want to know that. Josh: We were hanging out in Stockholm with that director, Adam Bhala Lough, who made Weapons and that Lee Scratch Perry doc. He said, “You guys don’t realize but there are no middle movies anymore, no $6 million movies. There are $80 million movies and under $250,000 movies. So we are grateful that we could be so free in the shooting process. We were allowed to emotionally experiment and do whatever we wanted. We could just keep shooting and shooting. I don’t even know what the final budget was on this movie, but if this is the biggest budget I’ll ever see, I’m fine with that. The budget was never a limitation on the movie, except for the paper tornado scene. A friend said, “I wish somebody would give you $2.5 million dollars just so that paper tornado scene could have been four stories high.” And yeah, I would have loved to have closed the block and had massive blowers and much more paper. The one shot I wish we had is a piece of paper traveling through the sky. And I wish we could have had steadicam sometime. Benny: But at the same time, we did have a rented apartment on 35th Street that we completely had free range to transform into a museum of our childhood emotional ideas, and that was our set. For months we could go there and do rehearsals. Filmmaker: So even though you are working with six and not seven-figure budgets, budget hasn’t felt like a limitation? Josh: The interesting thing about wherever independent film is going — I’m perfectly okay if producers are standing behind directors doing these highly personal movies. Not narcissistic, self-involved movies, but highly personal movies you can have free reign with. The idea of a production based on feeling and intuition, I really like that. I’m hearing of people making movies for $80,000, $1000,000 and sometimes shooting film, and if those are the big budgets of this new free filmmaking movement, I’m totally okay with that. I think that’s interesting. Most of the stuff I’m seeing, however, is not taking the risks that I want to see. I want to be so emotionally mixed-up about a movie that I can’t turn away from it. Filmmaker: Do you feel like you know your audience and have a relationship with them? Josh: We’re starting to, at least a little bit. Changing the title, that’s something we are doing in conjunction with an audience. We understood that Go Get some Rosemary was a title for us, and it wasn’t translating. We learned that at Cannes. It was kind of alienating and too esoteric. It was playing like a “gotcha” title, and our movies aren’t heady like that. Daddy Longlegs was Ronnie’s suggestion, I think it has a jazzy silliness but at the same time it has a sadness to it. The idea of having long legs is a weird optimistic phrase. Benny: It’s clumsy. There’s something funny about being clumsy, but you can always fall over. Josh: We just got our first sketches of the French poster, and they’re naming it Lenny and Les Enfants: “Lenny and the Kids.” Nobody can name this movie! This Greek festival named it something they wouldn’t translate for us. Not being able to name something is the biggest compliment — it’s a sign of uniqueness. But going back to audiences, when we were in Cannes, this young French guy, like 20, comes up to us. He had seen The Pleasure of Being Robbed, and he said, “When I heard you made a movie about a dad and his two kids, I thought, this isn’t underground.” I hate that expression! What does that mean? It’s not underground because it’s about a family! What does “underground” mean — that it has to involve young distraught people? And then I realized that people judge movies based on the demographic they see on paper. They see a father and kids and think it’s for families. But I do think this movie has a really weird reach. The people I’m most interested in hearing reactions from are middle-aged parents who are totally affected by the movie. And people who think, wow, I’m so disheveled I could never imagine having a kid. That’s where I come at the movie from. My dad was my age when he had kids. Jesus, that seems like a project. I think of that every time I walk down the steps of my apartment, like, wow, I could have a kid upstairs!

# posted by Scott Macaulay @ 1:30 PM

Wednesday, January 27, 2010

HIS AND HERS' KEN WALDROP |

By Alicia Van Couvering

Ken Waldrop’s His & Hers is a documentary focusing on 70 women from the Irish Midlands, arranged chronologically from age 0 to 90, telling small stories about their lives. Irish Midlands women, being funny, sarcastic, charming and warm, are good subjects; Waldrop knew that because he grew up the son of one of very funny and sarcastic Irish Midlands mother. He constructed the film to mirror his own mother’s life; the women speak of their marriages in their twenties, their sons, and, finally, their husbands and these men's deaths. Some of the interviews are about tiny things (who controls the remote control), and some are directly about the big issues (how you never stop feeling the loss of your husband); some are hilarious, some are heartbreaking. All of them are about love, to some degree. One of the central goals of independent filmmaking is to construct a series of small moments that add up to a much larger truth. The tiny moments we get with the adorable ladies of His & Hers add up to a small miracle of a film — a deep, emotional meditation on the universality of human experience. Filmmaker: Your movie made me cry and cry. Waldrop: OK, that’s a good sign! You know, we all have mothers, we all have grandmothers, we all have younger people in our lives, so I think there’s something in there for everyone. But I didn’t go out to make such a universal kind of thing (laughs). Making these choices, I was so worried, and my producer Andrew Freedman was just like, “Ken, this film is so low budget, if we fail, we should fail while doing something that is a little bit more dangerous.” But at the time I was so apprehensive. Filmmaker: How did you come up with the idea? Waldrop: You know, the film started with my thinking about my mother, because she had such a happy marriage, and she became a widow in her sixties. I thought, “It might be interesting to try to create a life’s journey in the same sort of way I’d been making my short films — with vignettes, [in a documentary style.] I used my mum’s life as a kind of structure. I wanted to make a film that was devoid of divorce and big bad things. I wanted to explore the ordinary, to try find this extraordinary journey that we all take if we’re lucky enough to find people to fall in love with. And of course there are ups and downs. There’s no doubt about that, but in general, I wanted to give a kind of positive thing. Filmmaker: Can you describe the structure of the film a bit more? Waldrop: Well, [since we’re using my mum’s life as a structure,] the story of the film was going to be the lifespan of a woman who was going to lose the love of her life when she got to her sixties. So the girl was going to be a baby, with her father as the most important man in her life, she was going to grow up, meet a boy, fall in love, get married. The husband passes away when she’s in her sixties, and they were going to have a son, who then was going to come out and look out for her, later in life. So it was always going to be, a girl grows up, the most important male in her life is her father, and growing up- Filmmaker: You know the fact that the facts of these different women's lives are all so similar didn’t even occur to me when I was watching it. It seems so obvious in retrospect. Waldrop: Yeah, I mean obviously, all the women had someone in their lives, but they had would have different variations. They all had big families, so they might have had four girls and two sons, which wasn’t the case if they were all single-parent families with just boys, but they all had a male child, [and that’s what they discuss in the film.] I wanted it to mirror my mum’s story. Filmmaker: Can you speak more about wanting it to be positive? The women truly don’t speak about any terrible things, except for death. All the conversations seem to be about love. Waldrop: I knew that it would be dangerous. Irish women, they’re always sarcastic about their husbands, but inside that, inside their little bickering and their problems, you can tell there’s genuine love behind their stories. I decided to limit again to Irish women, and Irish Midland women. Obviously there’s all sorts of ladies in Ireland, and all cultures and creeds, and I started to worry that the film wouldn’t represent all North Irish people. And then I thought, “That’s crazy, I’m just going to make the film, and these women are just going to remind me of my own mother." And in fact, they all live no further than about 60 miles away from each other. This was because we cut the budget and didn’t have enough money for petrol, so we put our base down in a village and looked for women there. Filmmaker: What other budget limitations did you have? Waldrop: Well, I really, really wanted to shoot on 16mm, I wanted to work with the constraints that that would impose. So I only had ten minutes for everybody’s interview. Filmmaker: Oh my goodness. One roll of film per lady.  Waldrop: Waldrop: Yes, including all the cutaway shots and all else. So you can imagine how stressful that was. And we were doing two people per day, so we only had four hours with each character, because we’d have to move on in the afternoon. So it became a bit of a military organization, because there were only four of us. For that reason, we decided, “Okay, we’re going to shoot during the day, indoors, because if it rains we won’t be in trouble.” It was a real team effort. We went home every night and cooked our dinners, and we’d look over the rushes from our little monitor, we’d discuss what we got that day, and consider the next two days’ characters. Because we weren’t shooting in sequence, we’d have to kind of go back and forth in the story, and work out what we talked about. In a way, it was a mundane, trivial life, and I’d half complain, you know, “That lady is talking about her car,” but I knew that we needed to talk about the car, just in case, because that was a way into the next story. I needed those little kind of clever edits that would keep the audience engaged, to make sure the film kept a kind of flow. After four or five characters, we started to make choices that we thought could lend itself to kind of creating this overall face of the film that exists in it. Of course there were ups and downs in the process, and some characters didn’t work out, but we really had a good success rate. I think, as we filmed new characters, we only lost twelve, and kept 70. So good extras for the DVD. Filmmaker: One thing all the women share is a way of communicating that’s very funny, and very sarcastic, and they all seem to know how to tell stories about themselves in a way that I feel is particularly Irish — I don’t know if that would have worked for a group of U.S. women. Waldrop: I think you’re right. I’m from the Irish Midlands. My mum’s a Midland woman, I know all her friends, and I knew that especially when they talk about the men in their lives, there is this innate sarcasm, and these kind of weird games that Irish men and women have with each other. I knew if I could get through to that that there’d be something to have. But it was a question: I have four hours with these people, how do I get through to that and makes sure they’re not talking in their telephone accents, you know? It’s the first time these people are on camera ever in their lives, and they’re all very nervous, and they don’t know me. I sent them my DVD of my shorts, so they had some idea of where I was coming from. And of course, I made a film called Undressing my Mother, which had my mum naked in it. Filmmaker: Oh goodness. Waldrop: That did shock a lot of them. (laughs) Filmmaker: So how did you get past their "telephone accent?" Did you ask them all the same question? Waldrop: I said, “I want to talk about the simple things in life that connect you, to your son, husband, or father." So that was easy for people, because they thought I was talking about [the things that you use to control one another], whereas if I was like “I want to talk about your relationship to your husband,” they’d be like, “Oh God, no.” You know, I’d have to kind of meander my way into their lives. I would start my banter, would discuss my own life, and it just became a chat, as opposed to an interview. So I hope that’s what comes across.

# posted by Scott Macaulay @ 3:12 PM

THE ROMANTICS' GALT NIEDERHOFFER |

By Alicia Van Couvering

Galt Niederhoffer is no stranger to Sundance, having produced films that won awards there beginning in 1997, when Morgan J. Freeman’s Hurricane Streets won the Audience Award. As a founding member of Plum Pictures, one of New York’s most active independent film production companies, she has produced over a dozen films, including Grace is Gone, Dedication, Prozac Nation, Lonesome Jim, The Winning Season, The Baxter and After.Life. Niederhoffer grew up in New York, one of six daughters of a squash champion-turned-hedge fund maverick, in a rambling, eccentrically decorated house. In her first novel, A Taxonomy of Barnacles, Niederhoffer may have used her vivid and unique family dynamic for raw material; in her second, The Romantics (on which the film is based), she explores the family you make after you leave home: your friends. Lila (Anna Paquin) is marrying Tom (Josh Duhamel), and Tom used to date Laura (Katie Holmes), and Laura and Tom may or may not still be in love with each other – dramas that the remaining five of their best friends from college arrive to witness. The group gathers for the rehearsal dinner and spends one long night reliving their college memories and testing the boundaries of their new adult lives. Comparisons to The Big Chill are inevitable, but this is a film that’s less about reliving the past than it is about reckoning with the future. As the seven friends come together, fall apart and come together again, all in the course of one night, they repeat their favorite toast — “to our glittering future!” — and each time its meaning is different. Filmmaker: What were some of the pitfalls of the Romance Movie genre that you had to work through or fight against? Niederhoffer: I don’t think anyone with any sense of movies and books could write a romantic story without an awareness of its tradition. It’s hard not to allude to various hallmarks of the genre, so I find those references unavoidable but sometimes really interesting. But you always want to avoid cliché — so, [I was] fighting cliché, and when appropriate embracing it. There are moments [in literature and cinema] that can never be done better than they have been. All you can do is embrace it and acknowledge the debt. I really wanted to make a sweet, emotional, romantic movie — something that moves you and swells your heart, that makes you weepy at times [and makes you] walk out of the theatre feeling happy and like you want to go make out with your honey. Filmmaker: Just like a wedding. Niederhoffer: (laughs) Yeah, exactly. I mean these things have a purpose — they make us feel good, and they remind us of the universal fact that we all are pitting this enormity of emotion against the question of that emotion’s validity in real life. I’m still most interested in stories with a love story at the center. [A wedding] seemed like the best setting in which to explore a love story of heightened proportions, the proportions of love when it seems to be the only thing that matters – which is a quality of love that it loses once you grow up. Filmmaker: What was happening in your life when you wrote the book? Niederhoffer: I was just turning thirty, and I was pregnant with my second child — actually, I finished the manuscript the week before he was born. I was really settling into this new phase of my life, being a mom and an adult, I suppose, and maybe looking back on the period before that phase with some nostalgia and some romance. Things change so completely when you become a parent; all that stuff like Love and Heartache kind of leave the picture for a little while. I was in that new phase of being a responsible human being who had lost the luxury of all of that drama and, in a sense, frivolity. So I guess I was interested in reliving them, through this idea of retelling the old story of a rich girl and a poor boy and someone else caught in between. I also wanted to do something that just had more sincerity and more heart [than my first book]. Sincerity goes very easily to the point of sentimentality, and I wanted to ride that line, which is a hard thing to do. Emotions are as tricky in stories as they are in the real world. They’re big and unruly and often the very unattractive sign of absurd and compulsive narcissism, you know? That quality is so true of young people and their emotions that you really have to navigate it with some care. The question kind of becomes: are young people fools, or are young people honest? Filmmaker: Jane Austen territory. Niederhoffer: It’s interesting that you would mention her because my first book was a real homage to Pride & Prejudice — but that’s why I think the Romantic period was so interesting to me, and why I had an epiphany moment when I figured out the title, and the central metaphor of it; two of the characters keep going back to this poem from the Romantic period. The Romantic poets were so interested in emotion — the importance of emotion, the placement of emotion, and the objects of it. They were reclaiming emotional intensity back from the Church, back from organized, institutional notions of love, and putting it into all sort of different things: nature, death, inspiration, the act of writing, and romantic love. Filmmaker: Do you agree that the story is one of six people all trying to decide how to deal with their emotions, or whether they want to deal with them at all? Niederhoffer: Yeah, that’s an interesting way of thinking of it… The movie, at its best, is looking at the various ways in which we handle emotions in our lives, and how that serves us and serves an individual. Another weird thing that happened in the mid-19th century is that emotion became defined in such a way that you could almost say it was invented. You have the Victorian era, and Freud, and suddenly there’s this totally new definition of the human heart and the human head and a narrative put in place about the fight going on between them. That’s a dramatic construction; that’s a story we tell ourselves about how people work and how our bodies work. If you accept that definition, which is pretty absurd, it becomes a way of understanding people and dramatizing the choices they have to make. Each of these characters is fighting their way through the choice they have to make. Filmmaker: How did being a producer prepare you for directing? Niederhoffer: Being a producer made me incredibly grateful for the opportunity, because I know how hard producers work — and all of our producers just worked their asses off, especially because it’s such a hard time to get a movie made. Like all movies, it was a little rocky getting it going, and I was so scared it wasn’t going to happen. So when it finally did, when everyone pulled through and worked so hard, I just was crazy with gratitude and understood that I had to carefully assess the battles that could not be won versus the battles that needed to be fought. It made me a little more humble and a lot more practical. Filmmaker: The thing I least envy about directors is the pressure on them to think creatively in the midst of this overpowering, relentless production machine. Niederhoffer: I think that’s the hardest thing. People are right to say that the best director is the decisive director, but I realized something about that. Sometimes being decisive means saying, “Hold on one second, I need to think about that.” Sometimes it’s not best to just shout out an answer; your gut sometimes does need a good 30 seconds to hear itself out. Everything is so accelerated and rushed, and that’s also part of the thrill of filmmaking — you add to this incredible mixture of people and limits and opportunities this crazy time thing, where every second costs thousands of dollars. That adds this “game” quality to the whole thing, like you’re playing this game of Tetris, trying to solve a new problem every minute. Filmmaker: How did you come up for the aesthetic plan of the film? Niederhoffer: That was the result of an incredible, really joyful collaboration between me and the core creative members of the movie – Sam Levy [the DP], Tim Grimes [the Production Designer], Danielle Kays [Costumes], and now Jacob Craycroft the Editor. We had one of those awesome experiences that you dream about, that I had seen other filmmakers have. It was a weird kind of echo of the story, the way we came together as strangers and were thrust together as a group of friends, and suddenly we had to listen and share and argue and disagree and concede, and it was all the things that the movie was about; being inspired, being moved, and becoming emotional because of a person or idea that takes you out of the mundane existence of daily life. Filmmaker: What was it like working with this ensemble cast? Niederhoffer: The magical, transporting, very intense thing that happened with the key creative crew happened again when the actors arrived. It was so intense, the exchange that happened between myself and all of these people, so much so that I would sometimes forget… I would think, “OK, I have to do the democratic thing and find out what everyone agrees on here,” and then I would remember that it was my right and responsibility to the movie that a clear vision be upheld and described. You hear about directors who are totally open and kind of defer to the actor, and others who are completely rigid and ignore the actor in favor of their original vision. I found early on that while it is essential to maintain a clear sense of your gut — I think that’s what vision means; what is your gut, after you take that second to ask yourself, “What is the best idea here?” — that right before that, you absolutely must listen to the best idea. Because if not, you might miss it. And often actors do have the best idea about blocking or a line or a scene, and it’s absolutely critical to pay attention. I found that whole interchange, first with my creative collaborators and then with the actors, really thrilling, quite emotional and utterly taxing, but ultimately very awesome.

# posted by Scott Macaulay @ 12:31 AM

Monday, January 25, 2010

SUNDANCE SENIOR PROGRAMMER SHARI FRILOT TALKS NEW FRONTIER |

By Alicia Van Couvering

Tasked with “celebrating experimentation and the convergence of art and film,” the New Frontier section at Sundance has been exhibiting feature films and installations for the last four years. Shari Frilot is the programmer, and spent the entire year reviewing work from new artists, figuring out which part of the ground being broken she wants to put in front of the Sundance audience. How to show film art in an art film context? Frilot tries to make sure that the artists all “speak the same language” as cinema. This year, the spotlight artist is Pipilotti Rist, who creates video work of massive proportions, having recently filled most of the ground floor of the Museum of Modern Art in New York City with a multi-screen project that invited you to lie on a couch and let envelop you. Rist is showing her feature Pepperminta, as well as using the same project for a live installation. Another trend: two films — Oddsac and All My Friends are Funeral Singers — seem to be representing the future of music videos: whole features built like albums, that will tour with the bands (Animal Collective and Califone respectively) and replace the short-form promotions they used to do. There are live documentaries, interactive Google map shows, art that you need night vision goggles to see, festival-long experiments in remixed cellphone video… there are more differences between this work than there are similarities, but collectively, this is the work at the festival asking all the questions. Filmmaker: How is this year’s programming different from the years before? Shari Frilot: We definitely charged ourselves to make something very different from the years before. The theme this year is "breaking out." Breaking out of old forms, old infrastructures, breaking out completely from the screen of presentation — that is, breaking off of the esteemed cinematic presentation and integrating into the realm of walking and talking. Where is the cinematic image as you walk through your everyday life? The shows this year are much more sculptural, [the exhibition] overtly engages the body, in really intense and physical and sensual ways. Pippiloti Rist’s installation is an entire red room, with beds in it (pictured above: Frilot, on left, and Rist). Filmmaker: She’s a great artist to showcase in this environment, her [video] work is so enveloping… Frilot: She’s our Artist Spotlight this year, she’s our example of an artist and a filmmaker who’s coming to the festival and platforming her project in a way that I’ve never really seen anywhere. She’s showing her first feature film, Pepperminta, and we’re showing it in the normal Sundance theaters in the more traditional way, and she is also constructing a fully immersive installation that is directly related to the film in the New Frontier space. So there is a visual world that you can enter in two ways with her project: one through a narrative arc in a [traditional theatrical environment], and one where your body is explicitly engaged with a kind of sensual, luscious, red lounge with beds, and the images from the film completely surrounding your body. I had hoped that [these ideas] would resonate with people who are looking for answers in this new, rewired landscape that we’re dealing with in the industry. Filmmaker: One reason that I love your programming is that it’s not literal, you know, like, "This is the kind of iPhone movie that people are making." Frilot: Oh gosh, I take that as a huge compliment! Filmmaker: Well I imagine it’s very hard to contend with a film industry and the art world and merge them in a way that resonates with the Sundance audience. Frilot: Well, honestly, I’m following the artists, and I’m following the filmmakers, and they’re the ones presenting sophisticated visions. I can’t take that credit. My job is not to build an art exhibit, my job is to build an alternative universe at Sundance, a kind of festival within a festival, with the support of the community and dialogue and discussion and the artistic inspiration around the evolving cinematic cultures. It’s about creating a [space] where people can get ready for thinking about a different way about the cinematic, to kind of disengage to reengage. But [the artists] have to be speaking the same language that filmgoing audiences have, in a way. It really is about experimentation. How do you present the cinematic image with an independent vision to film festival audiences, how do you do it? And how do you do it in a way that it doesn’t turn audiences off, but turns them on to something new? Filmmaker: How has your thinking abot it changed in the last few years? Frilot: I’ve always approached the question by referring to Audre Lorde, she’s a black feminist poet and theorist, and she speaks a lot about the power of the erotic, and erotic knowledge. And erotic is not about porn; she’s talking about the information that you have, that we all have, in our sensual selves. A lot of the artists this year are dealing with the sensual, and the pleasure principal — how do our bodies engage with the moving image? The site of our cinematic culture is around the body, it’s around the moving body, it’s changing our body. There is a tremendous physicality to the work this year, and that resonates so strongly with that viewpoint. It will be interesting to see how people are going to respond (laughs). Filmmaker: Which of the pieces are good examples of those ideas? Frilot: Well, when I say sensuality I’m using as a very broad way of describing how you use your body to touch and feel the work. So a great example is the Post-Global Warming Survival Kit by Petko Dourmana When you enter the installation you walk into a completely black room, but there’s a tent in the room. It’s pitch black, unless you take the night vision goggles that were given to you at the entrance and put them to your eyes, and then you can see an entire landscape — essentially this seascape. The tent is the residence of a worker from the future whose monitoring the rising sea levels and taking notes and keeping a diary, and you can’t see any of this unless you have the night vision goggles because in the future. So, in the vision of the artist, we had to create a nuclear winter to keep the planet cool. So this is something that directly implicates the body — you have to touch him and walk around and go around somebody, and their residence, and where they live, and what they are thinking, and what they are doing, and getting into the interiors of the character, this would-be character. Filmmaker: Wow. Frilot: Another great example is a piece by Matthew Moore, he’s a farmer from Phoenix, Arizona. He grows lettuce and carrots and grapefruits, and his piece Lifecycles is actually something that will be installed at the Fresh Market Grocery. With his work, he strived to connect consumer activity, to connect the lifecycle of the produce to the object you are buying. So we’re planting a number of screens in the produce section of the market, so for example, if you wanted to go and buy some lettuce, above the lettuce there’s a video that he’s shot of his own crops, from seeding to packaging. You find yourself in what has become a rather cold experience in buying and shopping, and developing a more physical and connected relationship with the thing that you’re buying. Filmmaker: You could make a kind of reductivist comparison between that and Food Inc., which is a documentary about Where Our Food Comes from…. But, how do you think the New Frontier work relates to the other features? Or, as a programming section, how does it relate to NEXT? Frilot: The films in NEXT are pretty traditional indie films. They’re really creative, they’re straightforward storytelling pieces of work, and they’re made for really really cheap. They kind of remind us that a lot can be had with a little, and that actually plugs into the new financial landscape of what our business is, and that’s why it’s called Next. It’s really called Less Equals More, but we call it NEXT because it’s more media-friendly. Filmmaker: Like the "Next" distribution model. Frilot: Exactly, like the next distribution model, whereas New Frontier is where filmmakers are really taking risks in terms of the storytelling itself. A film that has to do with all of this [distribution, new forms of media] is All My Friends are Funeral Singers. It’s interesting, because it was conceived to have the form of an album, and it’s by the band Califone. Oddsac, which is by Animal Collective, is another example. All My Friends… was made to promote the new album, and they’ve been taking it on the road, doing concerts and showing the film, doing a live score, so that’s a model coming up out of the music world. This is a trend that you will probably end up seeing in other festivals. Filmmaker: It’s so true, and I’ve never thought about it. Rather than make a video, because the music videos is such a dying form, unfortunately, or a changing one. Frilot: It is a changing form, and I guess this is where it is evolving to, kind of full-scale, feature-length work, some more experimental than others. Then there are films like Double Take and Memories of Overdevelopment. Double Take is just a really super-solid essay film, about thinking of killing his doppelganger, and also thinking about the rise of television in society during the Cold War….. It takes all these different elements and puts them together and it’s very poetic. And Memories of Overdevelopment is about a Cuban revolutionary who is now negotiating his creative freedom and a sense of viability, as the world evolves past an age of revolution, that kind of militaristic terrain. And this guy is such a talent, Miguel Coyula. First-time filmmaker, and really just one of these films that was just born out of the head of Zeus, like fully formed. One thing I feel really obligated to talk to you about, that really warrants attention because it’s so fresh and so significant is Utopia in Four Parts. It’s a documentary that is essentially a performance of a live documentary. He presents the piece live, he does all of the narration live, and the musical score is done live, so it’s all within one room, and he’s there, so the film itself is a rumination all about utopia. it’s really about him tinking about the utopian dream as it has evolved during the twentieth century, of how he believes that today we don’t have great ideas anymore, and we don’t have this shiny optimism that we used to have for the future. The future now scares the hell out of us. Photo by Jill Orschel

# posted by Scott Macaulay @ 1:17 PM

Sunday, January 24, 2010

SMOOTH CRIMINAL: A LOOK INSIDE MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM'S THE KILLER INSIDE ME |

By Damon Smith

This piece was originally printed in our 2009 Fall issue. This piece was originally printed in our 2009 Fall issue.As a filmmaker, British writer-director Michael Winterbottom ( 24 Hour Party People, In This World, A Mighty Heart) doesn’t linger long in one place. Just consider the globe-hopping locations he shoots in (Scotland, Pakistan, Iran, Shanghai), the hyperkinetic pace at which he works (there have been 18 features since 1995), and the versatility of his films, which cover every conceivable genre from sultry neo-noir and dolorous period drama to near-future sci-fi and Gold Rush-era Western. But the restlessness extends to his personality as well. In conversation, Winterbottom is so voluble that he can be hard to decipher, the words spilling out miles ahead of his own thought process. He is, to be sure, an artist in perpetual motion. It’s late August, and Winterbottom has just completed principal photography in Guthrie, Okla., on The Killer Inside Me, adapted from the 1952 cult crime thriller by American pulp writer Jim Thompson ( The Grifters, The Getaway). The novel tells the story of a seemingly mild-mannered deputy sheriff in West Texas, Lou Ford (played in the film by Casey Affleck), who is gradually revealed to be a deranged personality bent on sexual violence and murder. Thompson’s key innovation in the book was his clever, insidious use of first-person narration, through which we come to understand Lou’s grotesque logic and self-estranged state of mind. Jessica Alba is Joyce Lakeland, the prostitute who willingly succumbs to the young peace officer’s kinky, sadistic charms, and Kate Hudson appears as Amy Stanton, Lou’s adoring, well-bred girlfriend. Like the townsfolk in Central City, she remains clueless about his homicidal proclivities — “the sickness,” Lou calls it — until, of course, it’s too late. “There’s something about the way Lou narrates his own story that makes you feel sort of close to him,” says Winterbottom, on the phone from the London offices of Revolution Films, where he has just begun editing footage with longtime producing partner Andrew Eaton. “You feel as well that’s something going to happen to redeem him. And what’s brilliant about the way Jim Thompson tells the story is you’re constantly feeling that you’re going to come to this moment of knowledge — and then the book ends. [ laughs]” Many, of course, regard Killer as Thompson’s masterpiece, both for its tawdry Oedipal twist on psychopathology — repressed memories of sexual abuse figure prominently in Lou’s confessional monologue — and its cunning inversion of oafish, country-bumpkin mannerisms. Even Stanley Kubrick, for whom Thompson penned The Killing and Paths of Glory (largely uncredited), called it “probably the most chilling and believeable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered.” But for Winterbottom, there’s a Shakespearean dimension to the story too, and he was keen to draw out the tragic human subtext of Ford’s wicked impulses. “There are stories about people who seem to live normal lives, love their children and wives, and then they decide to destroy everything, to tear everything up,” he says. “Lou is that sort of character. The people who he kills are quite close to him; people love him despite the fact that he’s been violent towards them. There are psychological explanations in the book, but it’s more the sense of the pointlessness and waste that violence creates, and the tenderness of the situation that attracted me.” In that sense, he agrees, the film echoes Butterfly Kiss, Winterbottom’s 1995 road movie about itinerant lesbian lovers whose serial-killing spree, while horrific, never eclipses our sympathy for them: “There are many elements of a love story we’re trying to make with The Killer Inside Me.”  THE KILLER INSIDE ME CO-WRITER-DIRECTOR MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM. PHOTOS BY MICHAEL MULLER. THE KILLER INSIDE ME CO-WRITER-DIRECTOR MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM. PHOTOS BY MICHAEL MULLER.Winterbottom has a reputation for unorthodox adaptations of classic novels. He has twice interpreted Thomas Hardy for the big screen ( Jude, The Claim), and his ultracontemporary tweak on Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, considered to be an unfilmable book, earned high praise from scholars and critics alike. For The Killer Inside Me, Winterbottom says he was attracted to the pace of the narrative (“Thompson is a brilliant dialogue writer and plotter… the story unfolds incredibly fast”) and decided he wanted to honor the verbal spirit and lean structure of the source text. “In terms of individual scenes, [John Curran’s screenplay] was very close to the book anyway, but the order had been changed. So my approach was to go back to the original story and really keep the film as accurate and as faithful to the text as possible.” Eaton and Winterbottom teamed up with producer Bradford L. Schlei for Killer, their first U.S. production, and originally intended to shoot in West Texas. But financial incentives led them to relocate to Oklahoma, Thompson’s birthplace, where they found well-preserved turn-of-the-century architecture that evoked the post oil-boom ’50s. “Obviously you respond to the landscape you’re filming, the places you’re filming in. Looking at archival material from the ’50s and going to visit the arid landscape in Texas where it’s set — and looking at the towns, the much more lush town squares in Oklahoma and Texas — we were trying to find some kind of palette to make sense of that.” Although Winterbottom has ventured into noir territory before with I Want You, he’s not wedded to maintaining rigid genre codes for the film’s visual scheme. “It’s not a particularly noir-looking film,” he says, adding that he used bold colors to outfit the actors, which he plans to desaturate in post. “It was very bright and hot when we were filming, so you have these bright, kind of flat, washed-out exteriors. And then the much more gloomy, dark interiors. But all of these things come from the natural way the story is and the locations, as opposed to being necessarily imposed.” Asked if he’s seen Burt Kennedy’s 1976 version of The Killer Inside Me, Winterbottom says, “To be honest, I didn’t realize there was a version when I read the book. I chased down the producers who have the rights and they said there was one. And by that point, because I was already hoping to make the film, I said I didn’t want to be doing a remake. So I haven’t seen it yet. In fact, I think I’ll wait till I’ve finished this and then watch it.” In the meantime, he has his work cut out for him, editing rushes, correcting color and choosing music (a mix of classical and Western swing from old radio broadcasts). But one thing is certain: By the time we lay eyes on Winterbottom’s Killer, he’ll have vanished like quicksilver into the next shoot. The Killer Inside Me is due in early 2010, with France’s Wild Bunch handling worldwide sales.

# posted by Jason Guerrasio @ 9:00 AM

LOVERS OF HATE'S BRYAN POYSER |

By Alicia Van Couvering

Playing in competition this year is Austin filmmaker Bryan Poyser’s Lovers of Hate, starring Alex Karpovsky and Chris Doubek as brothers, Paul and Rudy, vying for the attention of Rudys’ soon-to-be ex-wife, Heather (Heather Kafka.) Paul is enjoying wild success as the author of a Harry Potter-like series of children’s books, which are based on stories that Rudy used to make up for Paul when they were children. Rudy, who calls himself a writer but who seems never to have written a page, seethes with rage and resentment; in fact, his wife is leaving him because of his bitterness. The brothers spend the film lying to each other, stealing each others’ property, and sleeping with each others’ wives, grasping at some way to finally feel that they’ve got the other beat. But it’s never clear what the point of the game is, and by the end, all they’ve done is gotten hurt and destroyed the playing field. Sundance viewers will recognize the sprawling Park City ski lodge where much of the movie takes place; the 7-11 shuttle stop even makes an appearance. This is Poyser’s second feature as a director; his first, Dear Pillow, played Slamdance in 2004 and was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award. Filmmaker: Have you had vengeful impulses in your own life? Poyser: I have had my share of relationships that ended poorly, and I’ve asked myself, if I could be a fly on the wall when my ex first slept with another person, would I run away or would I stay and take the torture? Rudy doesn’t react in a healthy way, at all, but that’s the part that I find really funny. He fails and fails and fails to try to break them apart, and then he finally succeeds, and then he realizes what a toll it has taken on the person that he was trying to get back in the first place. Filmmaker: How would you classify this film — as a drama, a thriller? Poyser: Unfortunately none the films I’ve made so far fall neatly into any genre classification — they’re all dramas, they all deal with human emotion. I’m interested in dark, serious subject matter but I want people to watch the films and enjoy them. Dark, funny films are what I’ve tried to make. Humor is a very useful tool to get people on board with you — it can deflate tension, it can get the viewer on the side of the character, it can prime them for some of the more serious stuff that you want to bring to the story. With Lovers of Hate, I wanted to make the first five minutes kind of broad. I wanted to make a movie that’s surprising and goes to unexpected places, which of course is always a challenge when you’re trying to get people interested in the movie, because what do you call it? My hope is that if people stick around and watch the whole thing, they’ll be surprised by the turns the film takes. Filmmaker: Was it hard to keep that tone consistent through the rehearsals and shooting? Poyser: Early on, a lot of people were pushing for the story to take a very violent turn, but I never wanted to do that — as soon as somebody does something deliberately violent or hurtful, they become a movie character, and not someone relatable. I was more interested in emotional violence, the psychological torture that [Rudy] tries to put them through and that they are inadvertently putting him through. Filmmaker: You’re very entrenched in the Austin indie film scene, which usually means working with very little money and a very small crew. Do you feel hindered by small budgets? Poyser: I do have the experience of working on a bigger film — The Cassidy Kids, which I didn’t direct but was very involved with in the writing and producing, was a crew of 50, with 35 speaking parts. Sets were built; it was a “real” movie. It was a huge challenge and an amazing education of how the hierarchy of a movie set works. It’s really there for the director to not have to do anything but direct. But it’s also a giant machine that’s very hard to stop if it’s going in the wrong direction. If you change your mind on a tiny movie set with five people, it’s a hell of a lot easier than if you want to turn around a crew of 100 people who have all been working for one goal. In a way, making it with a more realistic and humble attitude made the work a lot better, because I wasn’t so focused on where the film was going to go when it was done, but on the work itself. Filmmaker: Can you think of any lessons you took away from that production that you used on this? Poyser: Rehearsals, for one. We had no rehearsals on Cassidy Kids, and it really made things difficult. The characters in Lovers of Hate are supposed to have known each other for years — we did about a month of rehearsals, meeting two or three times a week for a few hours every time. It wasn’t about working on the script, it was just about getting to know each other. We played theater games, hide-and-go-seek, relaxation exercises, silly stuff, to just make us feel comfortable with each other and build this family bond in a month and a half. When we were in the house I made Alex and Chris share a room, like brothers, hoping that they would get pissed off at each other. Filmmaker: For me, the film was less about sibling rivalry than it is about male competition. Poyser: I don’t have a brother, I have a sister, and though we did have a similar creative childhood in the way that Paul and Rudy did — but yeah, I think that as closely knit and collaborative the independent film world is, we’re all competing for the same very limited amount of attention and resources. In a way, writing the movie was a process of me examining jealousy, a feeling that everyone has but not many people quite know what to do with. Filmmaker: The film made me think about one aspect of success, which is that if you do become successful, even if you believe you were very lucky, you still believe that you were rewarded for good work and capability. And it’s very easy to judge those who are less successful than you, or feel that you can see clearly the reasons for another person’s lack of success. Poyser: Yeah, I mean one part of my job at the Austin Film Society is to administer a grant for state funds for filmmakers, which has gotten very competitive. I have been fortunate enough to get grants from this group early on, but there was a time where I felt like I was just not included. I felt like I was not getting the recognition I deserved. When you’re young, you think you can upset the apple cart so easily. One thing I definitely learned from my mom, who was an illustrator, is that rejection is a part of life as an artist. Your job is to go out and try to get what you want and be rejected over and over again. You have to take those rejections and turn them into fuel to keep you going. The rewards are so paltry, and they end up costing so much — for instance, I am dropping a lot of money to come to Sundance and have this experience. I’m thrilled to death, don’t get me wrong. But before making this particular film, it did take a while to get over the experience of making The Cassidy Kids, which was disappointing for a variety of reasons. But eventually I thought, if I don’t make another feature, I will kick myself forever. In a very simple way, making this film was a way to tell myself to shut up, and be working on something, rather than sitting around and feeling worthless for not working on something. Filmmaker: Neither brother in the film, either the unsuccessful writer or the successful one, are made happy by writing. And neither of them, even though one is a complete failure and the other is a huge success, seem to ever have been humbled by failure. They’re both terrified of failing. Poyser: You could say that they don’t actually want what they say they want, but just that they want to get back at each other. I tried to make something about selfishness, which is something that all artists have to contend with in some way. At the end of the day, all three of them get a little bit of perspective on the way that their selfishness has hurt other people. Hopefully it leaves each of them in a space where they can rethink their actions.

# posted by Scott Macaulay @ 2:22 AM

Saturday, January 23, 2010

WOMEN WITHOUT MEN'S SHIRIN NESHAT |

By Livia Bloom

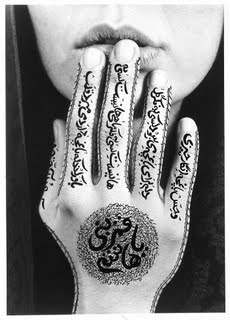

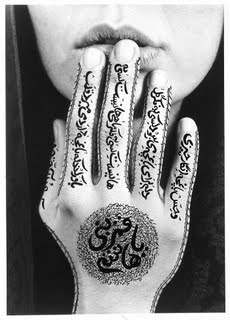

UNTITLED (WOMEN OF ALLAH). PHOTO COURTESY OF GLADSTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK. UNTITLED (WOMEN OF ALLAH). PHOTO COURTESY OF GLADSTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK."It’s very flattering to be interviewed by a film magazine as opposed to an art publication," said Shirin Neshat. "I am very flattered anybody would think it’s worth talking to me." Widely-acknowledged as one of the most influential contemporary Middle-Eastern artists (and apparently one of the most modest), Neshat and her work are staples of museums and galleries around the world, while remaining relatively little-known in film circles. That changed this year when she burst onto the independent international film stage with her first feature film, Women Without Men. The narratives of four women in 1953 Iran are interwoven in the film, which was seven years in the making. Each character comes from a different background and social class; one by one they are drawn together in a mysterious, isolated garden outside of the city where they find solace, comfort, and family in one another, at least for a little while. Women Without Men won the Silver Lion for Neshat as Best Director at this year's Venice Film Festival, and will make its American debut at Sundance this January. Forbidden to return to Iran, the country of her birth, Neshat studied at Berkeley and now lives in New York. Her multinational background is mirrored in the film: here, Casablanca stands in for Tehran (where she is not permitted to film); the producers hail from Europe, and, like the director, the actors are primarily Iranian emigrés. Dream logic and juxtaposition order Neshat's video installations and photography, and this is also true of Women Without Men. Based on a slim, brilliant 1989 novella of the same name, the film's tone differs from that of the book. They are companion pieces, like versions of the same song by different bands. Although both employ many of the same characters and surreal, magical story elements, the spare, unsentimental prose of the book, which is frequently interspersed with single lines of thought or dialogue, is very different from the serious, lush, and highly-stylized aesthetic that defines Neshat's film. The evolution of her intense, ritualistic imagery can be traced back through previous work. Women of Allah, an arresting series of photographic portraits of women in black chadors holding guns, swords, and flowers--including Neshat herself--featured detailed Persian calligraphy filling in positive and negative photographic spaces. In 1996, Neshat turned her attention to video. Shooting on 35mm film that was then transferred to video, she has created 18 single and two-channel digital installations, many using dual or opposing projection. The pieces have names like Rapture (1999), Passage (2001), and Turbulent (1998), the latter a split screen singing competition between a man and a woman that transgresses against Iranian custom that prohibits women from singing in front of an audience of mixed genders. The piece won the International Award at the Venice Biennale International Golden Lion.  TURBULENT. PHOTO BY LARRY BARNS, COURTESY OF GLADSTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK. TURBULENT. PHOTO BY LARRY BARNS, COURTESY OF GLADSTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK. began its public life as a series of individual video pieces named after its main characters: Mahdokht (2004), Zarin (2005), Munis (2008), Faezah (2008), and Farokh Legha (2008). The videos were shown in darkened gallery rooms that alternated with brightly-lit spaces displaying large-format photographic still images. Landscapes featuring oceans, cities, gardens, streets and homes were depicted vividly along with the gazing, searching, characters who are simultaneously archetypal, symbolic, and individual. The characters evoked questions of desire, beauty, history, and ambition with their staring eyes and detailed settings, props, and costumes. For the artist, the pieces are emotional touchstones, visual bridges between motifs from Neshat's homeland and America, her adoptive home. The perfect places to explore them are the movie theater and — of course — the film magazine.  WOMEN WITHOUT MEN DIRECTOR SHIRIN NESHAT. WOMEN WITHOUT MEN DIRECTOR SHIRIN NESHAT. It’s so strange to finally wake up at your own house after much traveling—sometimes I wake up I don’t know what country I am in or what time it is. (Laughs) This morning I woke up and was in a state of zombie.

Filmmaker: Oh no! Neshat: It’s so nice to wake up with your own apartment. I didn’t even leave much today. I’ve lived in so many horrible places that it feels good to finally be here. I think I paid my dues in New York. I’ve lived in every possible corner that was filthy or loud! [ Laughs] Filmmaker: Really? Your apartment here in Soho is just lovely... What was your worst New York apartment? Neshat: I remember living in the East Village, several different locations, but once above a punk rock nightclub, and they were just always driving me crazy. That was on Avenue A and Second Street. Then I lived on Avenue B and 12th Street, where there were a lot of people up all night. Then I lived in Chinatown, on East Broadway. It was really—it’s dirty, like the hallway hadn’t been swept for like 10 years. And we had a methadone clinic next door. So getting out of the house with a baby and a stroller, and there were heroin addicts next door, and they were spitting—it was just disgusting. And then I lived in Brooklyn. And then I lived on Elizabeth Street and then in NoHo. Those were really nice, but temporary... And finally here. Filmmaker: And now you’re home. Themes of home and family arise throughout the film; your female protagonists even seem to create a family of their own. Neshat: Yes, a community. Their garden was meant to be a place of exile; a place that these women could escape to, away from their problems; a place to be temporarily at peace. A shelter, a place of security, a new beginning, a second chance — these ideas are very poignant for a lot of us who are displaced from Iran. When I was young, 17, I left my family and never completely had a family ever again. Every seven years or so I have moved to a whole new beginning, a whole new situation [where I] try to feel a sense of security. But I’ve been a nomad. I hope it doesn’t change again, but it seems I regularly move from place to place in a big way, make new relationships and communities, and then move on again. The idea of nomadic feeling, always looking for an idea of security, is very personal.  SPEECHLESS. PHOTO COURTESY OF GLADSTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK. SPEECHLESS. PHOTO COURTESY OF GLADSTONE GALLERY, NEW YORK. Is it a surprise, if not a contradiction, to say that in exile, you have found a home? Neshat: How can you go about creating a new safe, secure or comfortable environment? First thing that happens, you surround yourself by Iranian people. But I’m not really a typical Iranian either; I was so young when I left that I’m very international; so for me, it’s really about balancing inside and outside of the Iranian community. To this day, I feel disjointed going in and out of the Western community and the Iranian community. I try to belong to both, but I always feel slightly an outsider and I believe that for me, as for a lot of artists, subjects that are very important to them peek their way into their narratives, characters and concepts. Filmmaker: How did you find the book that you adapted into this film? I look forward to reading it.

Neshat: It’s a very small one; you can read it in two, three hours. Though I don’t know if I should tell you to read the book. Which book have you ever read that has translated into film that you’ve liked? [ Laughs] When I decided finally to think about making a feature film, I looked for the right story. It's actually just what I’m doing now, for another film, which is really exciting. I was recommended a lot of books — like I am now — and scripts and stories to get inspired, and having worked with women’s poetry and having a feminist edge, a lot of people gave me novels to read by women. Shahrnoush Parsipour is one of the most important woman writers of modern literature from Iran, and I knew her writing as a young kid, a long time ago. Hamid Dabashi, a friend and scholar at Columbia University, handed me the Farsi version of Women Without Men and said, “You should really read this.” All Shahrnoush’s literature is surrealistic, magic realism. She has this incredible imagination, and her writing is unlike other literature that I’ve read. It’s really Iranian, rooted in Persian poetry, mysticism, religion, politics and historical events in Iran. Yet at the same time, she has one foot in universal, ephemeral, timeless, existential, and philosophical issues. I realized that it was the right story for me because in my work, I’ve asked deep personal, philosophical questions as a person and as a woman. I've also engaged with larger issues that are above and beyond me, too. Shahrnoush invented these characters according to some of her own mad ideas, and then I took them and I shaped them according to mine. This novel is set in the city of Tehran in the 1950s. It begins with very important historical events in the city, and then we come to the orchard, a completely different space. In my other work, these paradoxical elements were also really strong. Of course, I knew how difficult it was going to be to re-adapt a story that involves five protagonists and much historical material. But these were my initial and fundamental attractions: the book’s political and poetic properties. Filmmaker: What spoke to you about the four central women characters? Neshat: I think that the writer did a great job of choosing very interesting, diverse characters — socio-economically diverse as well as diverse in the type of dilemmas they have as women. Shahrnoush and I talked a lot about what childhood is like and how deep psychological issues of the body can be. As a first time feature director, it was interesting to think about how to develop their characters and think of them cinematically. For example, Munis is interested in activism, social justice, issues that are larger than her personal needs and her own narcissistic life. Like her, part of me always wants to be involved in activism; really, really wants to get very angry; and wants to do something for others.  WOMEN WITHOUT MEN. WOMEN WITHOUT MEN.With Zarin, it’s a question of her obsession with the body and her feelings of shame. [In response to external] stigmas, taboos, and judgments, the woman self-punishes. I’ve always had problems with my body and so in a way, I’ve always embodied this. I physically get ill at times when I feel a lot of pressure, and have faced issues of anorexia, thinness, and the need to be desirable. Even Farrokhlagha, the middle-aged character in her 50s, is thinking still about vanity and wanting to be beautiful and desirable, wanting to start over again and be a pioneer. This is something that I think is common in most cultures, though perhaps it is particularly [powerful] in my culture. Women hit 50 — it’s over, you know? In some ways, I embody her dilemma. They’re narcissistic things, yet very human. It’s really undeniable that all of us want to beat aging and be desirable and admired forever…and that it’s just not possible. [ Laughs] With Faezeh, the part I like and identify with most is this question of the security of tradition and traditional life; the security of wanting a simple life that involves raising a family and having a husband. That’s something I’ve never really had, you know. Everything for me has been kind of bohemian. Filmmaker: Did you shoot primarily on location, or did you also use sets? Neshat: We shot everything on location, just a little bit of the green screen, where we had to do when she had to fall. In Berlin we did that. But everything was shot in Morocco. We really didn’t have any money to do any sets elsewhere. Filmmaker: Your 2007 New Yorker profile mentioned that you didn’t own a camera. You had your videos shot on 35mm and then transferred to video.

Neshat: Yes; I never even studied photography. I’ve always worked with a still photographer, or here, a cinematographer. I did not make the film alone. [Art is often] about finding ways of collaborating with people who can help,and in all the areas that you’re weak, to build more meat. I think the most important thing to mention is the collaborative part of this process. Shoja [Azari, my collaborator] and I worked forever on all the video installations we have done. When I chose to make this film, we co-wrote the script. Shoja has spent as much time on this project as I have and has shaped so much in the scenes. From the directing to the post-production, he’s been involved in every part of it, and has also helped me make this move from arts to film. I want to see that Shoja take the credit as much as me, because very often people see me. Now, he himself is about to shoot. His turn is coming now. He’s just turning his script into a film that I think he’s hoping to shoot in February. I’m supposed to be not in the driver’s seat, but in the passenger’s seat, to help him. For me, [photography and cinematography] are about framing. Everything is carefully framed. In the feature film, everything was carefully framed and discussed in advance, almost drawn. We worked with a great Austrian cinematographer, Martin Gschlacht, who was unbelievably involved in the process. The brains of this project were Shoja, me and Martin. Every single shot was dissected both in terms of the dramatic process of the acting and also in terms of the framing. Later, he was very involved in the color correction with me. For me, the lighting is very important, and he’s a master of lighting. With the bathhouse, for instance I really, really wanted a shot in a space that was a very high ceiling, like a dome from which we could pan down. I wanted to capture the bigness of the space. But to light such a space is really difficult. One earlier cinematographer said it was impossible. It was going to be completely sad to lose the space if you couldn’t light it, you know. I explained to him what I want, and the relationship of Zarin to these people. Martin said, “I can do it.” I think my very favorite shot of the film is when Zarin is on the ground, on the floor, and she’s completely nude and she’s just sitting like this, this naked body. Do you remember when the boy is looking at her? When we had these little boys there, it just seemed incredibly poignant to have this moment; it’s like a loss of innocence. She was so out of it. But for a little boy, to be confronted with a nude body in this condition is just devastating. I thought that was a very important shot. Filmmaker: How would you describe her condition?