Back to selection

Back to selection

Sets and the City: On the History of Smithereens

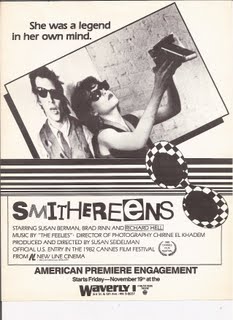

Susan Seidelman’s landmark 1982 debut feature, Smithereens, recently made its Cable VOD debut on Cinetic’s FilmBuff channel. It will soon be made available on iTunes, Amazon VOD, and more. Seidelman reflects on the origins of her Manhattan indie classic as it finds new audiences today.

I moved to New York City in the mid 1970s, to go to NYU film school. At that time the grad school was housed in a funky building on East 7th street and Second Ave — a space it shared with a rock club called the Fillmore East.

The mid-to-late ’70s was a transitional time in the East Village. The influence of the 1960s “hippie” culture was fading, and the “yuppie” gentrification of the 1980s had not yet begun. This was also during the time of the NYC bankruptcy crisis — when there was no money around to fix up neighborhoods or public spaces. That meant that the East Village had a lot of cheap apartments, cheap bars and clubs, abandoned and boarded-up buildings and a lot of disused outdoor space to put up posters advertising art shows and bands. As a result it attracted a lot of young, creative people — painters, actors, musicians, and filmmakers — who were looking for cheap space to live and work.

In 1979, after graduating from film school, I decided to make a film about this neighborhood and some of the characters that lived there. This became the basis for the film Smithereens. I had stayed in touch with my friends from NYU and we decided that if we pooled our resources, i.e. if no one got paid, we could make a low budget feature film shot on 16mm, for about $20,000. My grandmother had recently died and left me some money which was set aside for my “future wedding” — but since that wasn’t in the cards at that time, I decided to use it for camera equipment, film stock and lab expenses — and make a feature film instead. The final budget was $40,000 — due to unexpected stops and starts.

We began shooting in spring of 1979, with a script written by Ron Nyswaner and Peter Askin — based on a story by me — about a young woman named Wren (played by Susan Berman) who escapes her dreary life in New Jersey suburbs and comes to the East Village seeking fame and fortune in the Downtown punk-music scene. Because she has no discernable musical talent, nor does she think that’s necessary, she becomes the groupie to a shady punk rock star (played by musician Richard Hell) and a legend in her own mind.

The film was shot off and on over an 18-month period, as I ran out of money and dealt with various production problems. At one point, during rehearsal, the lead actress fell off a fire escape and broke her leg causing us to delay filming for several months. This meant re-casting and rewriting the script to accommodate changes in actors, locations, and crew members. Yet, all these stops and starts actually improved the film, since I was able to see what scenes were working and what story changes needed to be made. I was editing the film myself on a Steenbeck in my apartment — so during the months in between shooting, I could look at the edited scenes and adjust the script accordingly before going back out to shoot again. Had I not run into production problems, I don’t think the film would have been as good. For one thing, it would not have starred Richard Hell — since he came onboard during the six-month hiatus when we needed to recast the original male lead.

I wanted the film to be slightly stylized, but also capture the gritty reality of life in the East Village. I also wanted Smithereens to include some moments of irony and humor to counter-balance the harshness of Wren’s life. I would call the tone of the film “pushed realism.” The characters are real, the emotions are real, but some of the situations and art direction are “stylized.” The art director, Franz Harland, found gritty locations in the East Village and in mid-town (an abandoned parking lot under the old West Side Highway), which we then painted or decorated in a way to add a certain fantasy element. We wanted the film to capture a specific late 70s/early 80s punk graphic style. The look of the film was also influenced by the street fashion (what people wore to CBGBs or the Mudd Club) and street art — the “ransom note” graphics of the fly-posters advertising bands that lined the walls of Alphabet City, as well as early graffiti art.

Thinking back on it, there was something wonderfully naive about the way the film came together. We never thought about how (or if) the film would get distributed, or how it would be marketed. This was just a film I wanted to make that attempted to capture the spirit of a certain time and place. Fortunately, it ended up getting accepted to the Cannes Film Festival and then got picked up for distribution by New Line Cinema. But that was never something we calculated or even thought about when we first set out to make Smithereens.

The New York independent film community was much smaller back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and making an independent film meant that you did so with very little money. Often the director was also the producer, the writer, the editor and the distributor as well. You really were working independently. There were no indie production companies back then, or none that I was aware of. Many of the NYC indie filmmakers knew each other and shared information, actors and crew. Often one director could be seen acting in another director’s film. If there was any source of inspiration, it would be the spirit of the French New Wave filmmakers of the 1960s. The “let’s go out and shoot a movie” attitude. It was a very liberating way to work.

I think over the past 30 years, the independent film community has gotten much more diverse, complicated, corporate, and expensive. Some of that simple “let’s make a movie” spirit has been lost, although it can still be seen in some work, such as those by the “mumblecore” filmmakers. But we are now in a transitional time, especially with the collapse of so many of the smaller distribution companies, and it remains to be seen what the full impact of the Internet will be on indie filmmaking. However, there will always be people who want to tell visual stories – and they will find new ways to get their stories in front of an audience. We can no longer do “business as usual” – but as times change, as cameras get cheaper and the Internet becomes the great equalizer – new and creative possibilities emerge that makes me optimistic about the future.

Susan Seidelman’s other directing credits include Desperately Seeking Susan, She-Devil, Boynton Beach Club, and the pilot episode of HBO’s Sex and the City.