Back to selection

Back to selection

An Interview With Frederick Wiseman

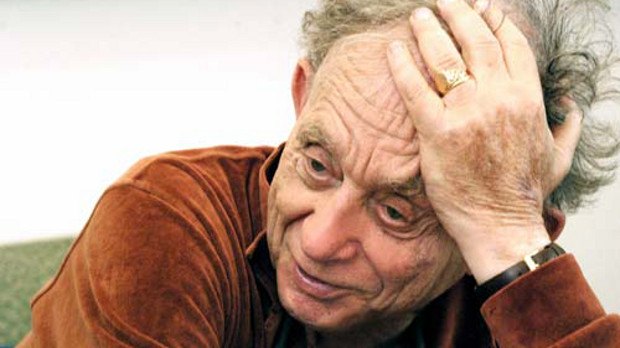

The New Year can be as much a time to reflect as it can be to project into the future. Some see the act of looking back as an integral part of moving forward. But on a brisk afternoon in Cambridge the day before New Year’s Eve, Frederick Wiseman resists this notion. The legendary documentary filmmaker has been making roughly one film a year since 1967, only taking breaks when funding difficulties, or in this case critical recognition, require him to do so.

Tomorrow night Wiseman is receiving the Legacy Award at the annual Cinema Eye Honors for his debut film Titicut Follies, which observed the appalling conditions at the State Prison for the Criminally Insane at Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Though completed in 1967, the film was withheld from the general public until 1991 due to its alleged violation of the inmates’ privacy. More compromising for the prosecuting government of Massachusetts, however, was the abuse it revealed by Bridgewater’s administrators.

The stress of that litigation now shows in Wiseman’s face—or maybe it’s just the jet lag. We meet the day after he returned from skiing in Switzerland, concluding a year of touring festivals with his latest film, Crazy Horse, about the Parisian cabaret club. The documentary couldn’t be farther away in subject matter and tone from his first one. Yet it falls neatly in line with his last two, La Danse: The Paris Opera Ballet and Boxing Gym, both dance films if you choose to characterize boxing as such. (Wiseman would) In Crazy Horse, Wiseman explores the professionalism and hard work underlying Paris’s legendary nude dance revue. Along the way, he explores the distinctions between art and commerce, as well as beauty and vulgarity.

January offers a rare opportunity to view Wiseman’s first film and his latest on the big screen. A Stranger Than Fiction screening of Titicut Follies will be held at the IFC Center on January 17th, followed by the opening of Crazy Horse at Film Forum on January 18th. The gap between those two films is substantial, but then, so is the gap between all of Wiseman’s films. Indeed, their diversity is their unifying characteristic. To see what I mean, check out his distribution site, zipporah.com.

Filmmaker sat down with Frederick Wiseman in his office to discuss Titicut Follies 40-plus years later, his working methodology, Crazy Horse and much more.

Filmmaker: You’re receiving the Legacy Award for Titicut Follies at this year’s Cinema Eye Honors. What is it like for you to recall that film 40 plus years later?

Wiseman: Well, it makes me feel how old I am. (Laughs) I’m glad to get the award. The Follies was made a long time ago, 46 years ago. I can recite all the dialogue. I can remember vividly the experience of being at Bridgewater and the legislative hearings and the trial. But I also have the same kind of intense memories of all the films.

Filmmaker: Are you able to separate your memories of the film from the litigation that held its release for so long?

Wiseman: They’re very separate. Making the film was one thing and the litigation was something else. The litigation was basically a farce, because the effort to ban the film—even though they succeeded for quite a while—was just an example of political cowardice and stupidity. I always thought of it as political theatre.

Filmmaker: What do you think it is about that film that has earned it a Legacy Award?

Wiseman: I guess the Awards Committee liked it and wanted to recognize the film. I am pleased that they did. They also know that I’m old. (Laughs)

Filmmaker: I’m sure it’s more than that. The film has stood the test of time.

Wiseman: Well, I’m glad it’s stood the test of time. Bridgewater was a horrible place. Although, compared to some of the other prisons for the criminally insane that I was familiar with at the time it was a Ritz Hotel. It may sound odd, but I don’t really think about the film that much, because I’m more concerned with what I’m currently doing always. Maybe when I stop working—which I hope never happens—I’ll be more sentimental about the past. But at the moment, it is just another film I made. It’s my first film.

Filmmaker: Your films have so many unanswered questions and so much room for interpretation. I’m curious how you interpolate within that process. When is your time to reflect?

Wiseman: Whatever “thinking” goes on occurs in the editing. There is not much time during the shooting to think about the implications and structure. I usually don’t begin to think about structure until I am six to eight months into the editing, and have most of the candidate sequences in close to final form. Also, I do not like to explain a film.

Filmmaker: I know you don’t.

Wiseman: Because I don’t think that’s my job. My job is to make the film as best I can, and what I think about the subject matter is what you see in the final film. That is my job as the editor. So much of film editing—or at least editing these kinds of documentaries—has absolutely nothing to do with technical issues. It has to do with identifying to yourself what you think is happening in the rushes. Obviously, it has to do with technical things as well, but at least 50% of editing my films has to do with an attempt at an analysis of human behavior. The basic question is “Why?” Why does somebody ask for a cigarette at a given moment? Is there an explanation for the choice of one word rather than another? What’s the significance of the dress that a woman is wearing? Why does a client come to a welfare center wearing his military uniform? Why does someone pause in mid sentence? Is there an explanation for a change of tone? I mean, these are the kind of evaluations one is always making in ordinary experience when you meet people. You have to make these kinds of evaluations in more concentrated form when you are editing. This same sort of evaluation is going on between us in this conversation. In film editing it is more formalized and constant.

Filmmaker: Do you enjoy the different meanings that viewers make of your films?

Wiseman: I don’t spend that much time with audiences, but I do from time to time. One of the ways I make a living is doing my little buck and wing in schools and colleges.

Filmmaker: What colleges do you lecture at?

Wiseman: Whatever college invites and pays me. I like to do some lecturing but not too much because it takes a lot of time and travel and is tiring. Over the years I’ve talked in many colleges, universities and public libraries.

Filmmaker: What do you typically have to say to your audience about documentary filmmaking?

Wiseman: One or more of my films are shown before I arrive. A film is also shown the day that I am present and I will use that to illustrate my talk. Also I sometimes show excerpts. I often take excerpts and reconstruct with the class—or the audience as the case may be—what my choices were in the editing, and why it was shot the way it was shot. One of my cliché responses is that editing is talking to yourself. So what I do is try to reconstruct with the audience the conversation I had with myself when I was editing, where I keep asking them the same “Why?” I ask myself.

Filmmaker: Does that question usually find a logical response for you? For example, Y follows X because that’s its chronology in time?

Wiseman: Editing, for me, always has been a combination of being very deductive and very associational. And if I’ve learned anything over the years, it’s that I should pay as much attention to the thoughts at the edge of my head as I do to the formal, logical and deductive. All the clichés are true. You can dream the cut. It can pop into your mind when you’re walking down the street, or taking a shower. I’ll tear what’s left of my hair out because I can’t resolve an editing issue. And I’ll go for a walk or I’ll have a nap or I’ll go back home and come back the next day, and “My God, there it is.” Without consciously working on the problem I will have been working on the problem. And whether the result is a good one or not, I don’t know. But it resolves it satisfactorily as far as I’m concerned.

Filmmaker: I’m interested in the importance of constraints to your work. You set rules for yourself, like setting your films within a defined geographical space. Are there are any other constraints that you place on yourself in the shooting or editing process?

Wiseman: Self-imposed constraints?

Filmmaker: Yes.

Wisman: I don’t know if this is a constraint or not, but I make the choice of not following one person. And I don’t accept any constraints from the subject, other than if somebody doesn’t want to be photographed I accept that without argument. I don’t accept any network constraints about length.

Filmmaker: And PBS has been pretty good to you about honoring that request.

Wiseman: PBS has been extremely good to me. The first movie on PBS was Hospital in 1968…So it’s going back 44 years there. And they’ve never asked for any changes or any cuts. But I took a hard line about that at the beginning. It hasn’t been challenged. And they’ve been very generous. Near Death is six hours, and they ran it all at once.

Filmmaker: Much of the complexity of your films comes from their duration, from the ambiguities that arise during the lengthy conversations between your subjects. I’ve heard you speak of preserving that complexity as matter of responsibility to your subjects. Can you talk about that?

Wiseman: I have an obligation to the people who have given me permission not to simplify the material in the service of some personal ideology which they may not share. And I take that very seriously, because when someone has confidence enough in me to let me hang around—either the person that’s in charge of the place or the person who’s involved in a particular sequence—I feel an obligation to treat them fairly (however subjective that term may be). Take Welfare, for example—and it is also true for many of the other films—the only time I ever saw the clients was when the sequence that they were in was shot. I mean, it’s not like with the ballet company where you’re hanging around for 12 weeks and you’re seeing a lot of the same dancers day in and day out, or La Comédie-Française, where I attended many rehearsals with the same actors. The workers at the welfare center knew that a film was being made and I saw them frequently, but the clients I often only saw once: the moment when the sequence they were in was shot. Nevertheless, I was able to shoot without objection the meetings between the client and the worker when very personal and intimate aspects of the clients’ lives were revealed. When I use such a sequence I feel an obligation to make sure that the sequence—again, it’s a very subjective judgment—fairly represents what I think was happening. For example, there is a sequence early in Welfare with a couple that is seeking emergency relief. The woman has a very unhappy family history and the man is a former welfare worker, is clearly lying about his personal experience thinking that his knowledge of the welfare system will make it easier for him to qualify. The sequence is funny and it’s sad and it’s very revealing about the welfare worker and the thin line between the welfare worker and the client. There’s a lot going on. But the original sequence was maybe 40 minutes. It’s about eight minutes in the film. So in cutting it I wanted to retain all of those complex relationships, but at the same time I had to condense it without losing the complexity and ambiguity of the actual encounter.

Filmmaker: I notice a difference in tone between your early films and your recent ones. Titicut Follies and Welfare, for example, reveal high levels of incompetence and sometimes injustice in the institutions they represent, whereas La Danse and Crazy Horse seem more focused on the successes of the institutions they represent. It’s tempting to say you’ve gone from being more cynical to being more optimistic. I know this one Errol Morris quote…

Wiseman: It’s a great quote. (Laughs)

Filmmaker: He referred to you as “the undisputed king of misanthropic cinema.”

Wiseman: But it’s a description of him. It’s not a description of me. Well, it’s not for me to say it’s not a description of me. But it’s certainly a description of him. (Laughs)

Filmmaker: Do you think there’s some truth in saying your outlook on life has changed over the years?

Wiseman: I resist saying that there’s a change, because I think each film is a response to the subject matter of the film. And I didn’t do a film about a great ballet company in 1967. If I did a film about the New York City Ballet in 1967 when Balanchine was alive, it would have been what you call an “optimistic” film because it would have been a film about a great artist at work. Similarly with the film about the Paris Opera Ballet. It is one of the great ballet companies of the world. For me it is irrelevant whether I made it in 1968 or made it in 2007, because the final film is a response to the experience I had with the dance company. So I don’t think it reflects an overall change. If I hadn’t made Titicut Follies in1966 and went to Bridgewater today, technically the film might be better, but I don’t think that the point of view that the film expressed would be any different if I found exactly the same things that I found in 1966.

Filmmaker: Is there a difference in the way you’re choosing your subjects?

Wiseman: Well again, it depends on the context in which you look at that issue. If you look at it that I’m choosing more arts-oriented subjects, then you can think I’m abandoning the earlier subjects. There were some French critics who didn’t like La Danse, for example, because it wasn’t “Wisemanesque”. What “Wisemanesque” is to them, or meant to them, was a film showing poor people being exploited by the state. Which means that they haven’t really understood some of the earlier films either. Because I think it’s much more complicated than that. The point being that each film is a response to the experience, and not because I’ve gotten softer or I’ve gotten less cynical or more optimistic. I like to think that I’m responding in each case freshly to what I find. I am also trying to make films on as many different aspects of contemporary life as I can and do not feel in any way restricted to a particular subject matter.

Filmmaker: Crazy Horse offers an interesting subject of response. The film walks a fine line between conceptions of beauty and vulgarity. Do you think of those categories as mutually exclusive?Wiseman: The real answer to the question is what you see in the film. But that’s one of the questions that the film poses. That’s why I think that—and some people laugh when I say this, but I’m not saying it ironically—despite the fact that it’s about beautiful women who are sometimes almost completely naked, it’s the most abstract movie I’ve made in terms of the ideas that I think that the movie is dealing with, among them what you just said.

Filmmaker: It’s a provocative film, not just in terms of its content but in terms of how it’s shot. There’s a lot of fragmentation of women’s bodies—a midriff or a buttocks. After a time these parts become so disembodied as to, yes, take on an abstract quality. But were you concerned that the framing could be seen as objectifying?

Wiseman: Well I think that’s too reductive, because one important aspect of The Crazy Horse brand is a woman’s ass! I mean, you see that when the women come in for their tryout, their casting session.

Filmmaker: That’s the one scene in which the choreographers and the directors are particularly dispassionate towards the women. Whereas the bulk of the film reveals a respectful relationship similar to that of the choreographers and the dancers in your ballet films.

Wiseman: Well, Philippe Decouflé, who is the principle choreographer, really treated the dancers quite well. He respected them, he trusted their judgement, he viewed them as collaborators.

Filmmaker: An off-center question: how would you define beauty?

Wiseman: I would resist defining it. (Laughs)

Filmmaker: Expected. Why did you choose to shoot the film in digital?

Wiseman: No money.

Filmmaker: That’s disheartening to hear that Frederick Wiseman of all documentary filmmakers has trouble getting his films made.

Wiseman: Everybody assumes that because I’ve doing this for so long it’s easy for me to get the money.

Filmmaker: Has it ever been easy?

Wiseman: There was one time in my career between 1971 and 1981 when it was extremely easy because the Ford Foundation gave Channel 13 two 5-year grants which were directed to me. Fred Friendly liked my films and he was in charge of the Ford Grants. Without his help and support my career would have been very different. For ten years, I could go from film to film without raising any money. All I would do is call Channel 13 and say, “Juvenile Court.” And they would say, “Okay.” And then I’d get half the money when I started shooting and the other half when I handed the film in. I mean, that was ten years of not singing for my supper. But that was over in 1981. So since then, like every other filmmaker, I have to make the rounds to the same eight or ten places where you go to try to get the money.

Filmmaker: Would you say it’s harder than ever to fund documentaries?

Wiseman: I think it’s harder for me than it ever has been. One reason is I think that people assume that I can get the money. But it’s not true. Because there are only eight or ten places in the world where you can go to get the money, and everybody goes to them. I have to go with my hat in my hand like everybody else.

Filmmaker: I’ll admit that I’m among those who thought you could get the money. I guess it’s wishful to assume that after applying to the same foundations you’ve been applying to since 1967 there would be a sort of designated “Wiseman fund.”

Wiseman: No. In fact, it’s just the contrary. I think that they think I’ll get it elsewhere, or they’ll want to give the money to younger filmmakers. I don’t know, because I don’t get an explanation. But I’ve been turned down a lot recently. And I may be self-indulgent or arrogant, but I don’t think my films have gotten worse. But it’s very, very hard to get the money.

Filmmaker: So how was your experience shooting in digital?

Wiseman: I think there’s a lot of bull shit in discussing the switch. The only thing that was partially true that somebody said to me was, “You’re going to shoot a lot more.” And I don’t know that that’s even true, because the two films that I’ve now shot digitally were both films where there was a lot going on. And I don’t remember any sequence where I ever said to myself, “Well, let’s go ahead because it’s only $35 for another hour.” I never thought about the cost of film when I was shooting film, and I still don’t think about the costs. It also came up once in a rather odd way, in a way that I think was uninformed. Somebody once wrote a review of one of my films—the film was almost four hours—saying that it would have been a better film and a shorter film if I had edited it on an Avid. And it was basically an assumption that the machine made the cuts.

Filmmaker: I’m not sure I get the criticism.

Wiseman: Well I don’t get it either. Because whether you’re editing on a Steenbeck or a computer, you have to make choices. The greater accessibility of the material on the Avid doesn’t give you any more choices. I don’t have any more choices on the Avid than I do on the Steenbeck. It may take me longer to try them all out on the Steenbeck. I can’t just type in the roll number and shot on a Steenbeck. I don’t think that that kind of speed and accessibility on the Avid is necessarily a good thing. Because when I had all the film rushes hanging on hooks on the wall it took more time. I had to find the film roll, put it on the Steenbeck, and roll down to the shot that I was looking for. But that wasn’t wasted time. First of all I was reviewing material, and second of all, I was thinking about why I was looking for what I was looking for. But when you edit on a computer, you go “Boom” and you get all 300 cutaways. There are advantages and disadvantages to that with respect to knowledge of the material.

Filmmaker: Does nonlinear editing cheapen the process for you at all?

Wiseman: It doesn’t cheapen the process. I deliberately slow myself down. I don’t think the result is any different. But there is also something very good about it. The other day I had to put together a foundation proposal, and I did it in two days. I had to use a lot of cutaways and it would have taken me two weeks to find and organize those cutaways on a Steenbeck.

Filmmaker: Can you talk about your upcoming projects? You’re directing another play, and you just finished shooting another film in UC Berkeley. What are you working on now?

Wiseman: Yes at the moment I’m editing Berkeley. The tentative title is At Berkeley. I’m going to edit it for a bit longer, and then I’m going to do [the film] in the morning and the play in the afternoon. The Berkeley film which was also shot on digital will be ready at the end of the summer.

Filmmaker: And what is the play?

Wiseman: It is about Emily Dickinson and called “The Belle of Amherst”. The play is a monologue. Julie Harris toured in it for years. It is a very well-written play, and with many of Emily Dickinson’s poems. Emily Dickinson tells the story of her life. And I have very good French actress, Nathalie Boutefeu, who is going to play Emily.

Filmmaker: So what keeps you going? You don’t show any signs of slowing down.

Wiseman: I’m busier now than I’ve ever been in my whole life.

Filmmaker: And you’re physically up to it—recording the sound, carrying the equipment, putting in 13 hour days, the works?

Wiseman: I’m able to do it because I try to stay in shape. I’ve always been a bit of a sports nut. I work out a lot. I ride an Excercycle, I lift weights, I walk a lot. If I am running around all day carrying equipment and trying to be reasonably alert, I have to be in shape. But also, I think it’s necessary to do that anyway, just stay in good health and keep the grim reaper at bay.