Back to selection

Back to selection

Ruaridh Arrow, How to Start a Revolution

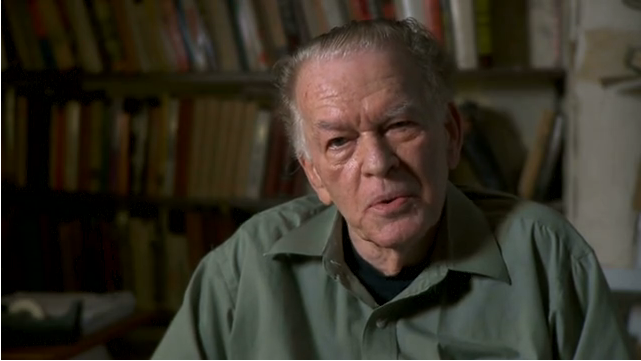

Although you’ve probably never heard of him, writer and professor Gene Sharp is one of the foremost scholars on grassroots, non-violent protest movements. The son of an itinerant preacher, the Ohio-born octogenarian, whose writings have informed the tactics of protest movement leaders from Serbia to Iran and the Ukraine to Syria, teaches at UMass Dartmouth. He lives a life of relative quiet and solitude, at least when revolutionaries from around the globe aren’t clamoring for his advice. In Ruaridh Arrow’s documentary How to Start a Revolution we get up close and personal with Sharp, who has drawn the direct ire of dictators and plutocrats on the far left and far right, from Hugo Chavez to the late Slobodan Milosevic.

Arrow’s film takes us from the quaint Boston offices that Sharp maintains with his assistant, Jamila Raqib, to various conflict points across the globe, where Arrow profiles the very people who put Sharp’s formula of unrelenting non-violent civil disobedience into action. In so doing, he links a broad cross-section of social and political movements together under the rubric of Sharp’s techniques. At the same time, he reveals to us a man of seemingly impeccable moral rigor, who, from the time he was jailed for protesting Korean War conscription (long before the anti-war movement in the States gained steam over a decade later), has been committed to non-violent political struggle.

Trained as a newspaper journalist, Arrow got his start in broadcasting producing news segments for the U.K.’s SkyNews, before he moved on to Channel 4’s Frontline-esque Dispatches series. He has produced documentary programs for the The Financial Times and the BBC. During the Egyptian Revolution, he reported regularly from Tahrir Square. His feature debut, How to Start a Revolution premiered at last fall’s Boston Film Festival, where it won a prize for best documentary. It opens at the ReRun Gastropub Theater on Friday.

Filmmaker: How did you first learn about Gene Sharp’s work and how did your interest in his work evolve into the desire to make this film?

Arrow: I’m originally a newspaper journalist. I don’t think of myself as a filmmaker. As a journalist, I was covering alot of the so-called “color” revolutions. I noticed that everyone was using the same tactics. I wondered why. At first I wondered if it was sort of a conspiracy — are there forces at work? — but when I talked to the leaders of these groups they were all using the same book, and that book was Gene Sharp’s From Dictatorship to Democracy. That was a few years ago.

Then I saw it used by the Iranians in 2009 before the Iranian uprising. It’s a very different country than the ones I’ve seen it used in before, and I thought that there was something in this, that this guy was obviously of extreme importance. He’s a writer first and foremost, but he’s maybe not the most obvious topic for a documentary because he doesn’t really go anywhere or do anything. It’s his book that’s going places, but he’s making a significant impact in very different countries. And therefore I felt like I had to go and make a film about him, just for the historical record – so that the story wouldn’t be lost.

Filmmaker: How did you go about approaching him? Was he at all suspicious or resistant of the project at the beginning?

Arrow: I had no in with him at all. Really I just called them out of the blue and got his assistant Jamila, and we talked about the project. I think they were kind of resistant at first because they had had so many bad experiences with journalists going down the whole CIA conspiracy theory track. So they weren’t sure. What I was saying is, “I want to make a movie about your work and your life as a whole,” although it didn’t really turn out like that. Nevertheless, that’s a big thing to hand over, all of that access to a young, relatively inexperienced filmmaker [who wants] to interpret your life. It was quite a brave thing. It took a while for them to get back to me, probably about a year after we’d been talking about it. He said, “I’m getting old now, it would be useful to have a film in existence to speak my words when I’m no longer able to speak them myself,” which is the point where I knew I had a great responsibility.

Filmmaker: How much help was he in leading you toward some of the other individuals we meet in the film who are part of various other non-violent protest movements, be it in Serbia, Iran or elsewhere? Did he have much input in other aspects of the film?

Arrow: He didn’t have any input. I knew that there was Bob Helvey. I knew the outline of the story, much of which involved things I had seen about Serbia in the Wall Street Journal in 2009. I knew the key actors were Helvey and Sergei Popovich. Although I needed his input to make sure the academic stuff was correct, I only wanted a very light introduction to the main principles, there is a delicate balance to be struck between going in depth and making the film essentially just a lecture. What’s interesting about the characters in the film is lots of people, revolutionaries from around the world, would go into that office, but they wouldn’t give me any names, or contact them on my behalf.

It was almost like a game of Battleship. I would go out and find leaders of non-violent struggle groups in various countries and then they would say, “Yes, I’ve been to Gene Sharp’s office,” and then I’d go back to Jamila and Gene and tell them that the person in question claims to have seen them and would they would be willing to talk about it. But they would never give me the people. So there is a strange editorial distance there, and it’s to do with the security of the groups that are trying to do this kind of work, which is very important.

Filmmaker: There has been an ongoing debate among various observers of the Occupy Movement here in the States, namely David Graeber and Chris Hedges, concerning the action of so called Black Bloc Anarchist groups who have been involved in various Occupy encampments and whether their somewhat more aggressive tactics are a danger to the movement. Your film touches on similar concerns about whether the media’s desire to latch onto a narrative in which anti-authoritarian protesters as unruly agitators hellbent on destroying private property is easily fed once people stray from a purely non-violent doctrine. Having examined these issues closely yourself, where do you fall on these issues? Can these movements be big-tent operations that condone a variety of tactics, perhaps some more or less aggressive than others, or do you think that straying from non-violence is dangerous?

Arrow: Yeah, I do. I came to this work fresh. I wasn’t really aware of Gene Sharp’s work in depth when I started out. When I talked to these various revolutionary leaders, their most perilous point during the Orange Revolution or the Serbian revolution was when people came to the table and said, “We’ve had enough of this now, we want a violent option.” Non-violent struggle groups are very similar in their organizational structure to terrorist groups in many ways. They have the same capabilities, are jammed with very smart people with great international contacts, and they can go different ways. At each stage of these movements, the leaders who used Gene’s work were able to go to the table and say, “We’ve got something else, this is peaceful protest but it’s more powerful than that, and it’s not terrorist action, so let’s try this first.” And it was a really important stage in diffusing what could have become a civil-war type situation.

My background is journalism and I work as a producer on SkyNews’ 24 channel, so I’ve covered these protests like the G8, and the fact is that 24-hour news is led by picture. You can have the biggest story in the world, but if you don’t have really good pictures of it, then it won’t lead the news. When a non-violent struggle like Occupy happens, it wasn’t being covered for a long time because nothing was really happening when they first set up on Wall Street. But when things started kicking off and windows were getting smashed, suddenly there was great picture from a news perspective. I’m not really attacking the mainstream media. I’m from it. I understand that news coverage is driven by exciting picture. Just a few people breaking a window can hijack your entire movement.

What Occupy has failed to do is come up with interesting ways for news media to cover them so that they get widespread coverage and can draw in the general population. They’re not doing the sorts of interesting and humorous skits and pranks and things, peaceful, non-violent ways of getting into the media, big publicity stunts, really innovative things that catch the public imagination. Therefore they were getting frustrated and breaking things. It’s a big danger that Occupy was falling into because Occupy needs to spread their message, they need to get more people on the streets — young people, old people, the grannies, the military veterans, everyone out onto the streets.

I was in Tahrir Square. As soon as violence broke out, the only people who stayed were the young men. The kids, the old people, they all left. Then it became very easy for the police and military to brand the people still there as agitators, as young thugs, because it was just young men throwing rocks. It was easier for them to then clamp down on the protests. As soon as someone in a black bloc at Occupy comes out and start breaking windows, the kids and the old people run away and go home and what Occupy is left with, at least on the news that night, are loads of young men breaking windows. And the next time they have a big march or demonstration the old people and the very young people don’t come out because they’re scared of violence, and therefore you don’t see on the news a picture of the whole of society working to counter the system, but what just looks like a small, fringe minority. So I think that’s a very clear example of how these sorts of things clearly make your movement weaker. If the whole of society can’t get behind you because physically they’re threatened by the actions of a few, than clearly that is going to dim your movement, because the movement relies on numbers.

Filmmaker: Given the brutality used against various liberation movements by authorities in Syria, Iran, Bahrain, Libya and even on the streets of New York City, Oakland, UC Davis, etc, do you think that the media narratives themselves – which seem to feed on an ideology that seeks to blame these protesters first for these sorts of violent clashes (despite the disproportionate capacity for and use of violence that tilts in the police and military’s direction) — are shapable in any way? Can they be made to offer perspectives from the protesters’ points of view?

Arrow: I think that that’s possible. One of the things that Gene struggles with, and this really isn’t in the film, is that a lot of people in Egypt said, “This isn’t a non-violent revolution because the police are attacking us.” Well, that’s a complete misunderstanding of the term “non-violent revolution”. A non-violent revolution can still be non-violent even if the police are attacking you. It’s just that you are non-violent. What I see quite a lot of, and my friends who are still covering these matters in the mainstream media see it a lot as well… Say Occupy Oakland goes out and it’s a completely peaceful march and then the police do a baton charge and they say, “Violent outbreak of protesting happened today in Oakland.” Well that’s not actually accurate; it was the police that conducted the violent activity. How we get the message across to the mainstream media? And how they report on non-violent struggles is really, really important because all they’ll say is, “Violence flared on the streets of Oakland today” without giving the entire context. That really doesn’t tell you the story of what’s going on there. It’s important for those groups to be able to properly articulate all of this to the media about their strategies and principles.

Filmmaker: How can the citizenry hold the media more accountable?

Arrow: Well I think social media is important here. It is challenging the pillar of the state media, it’s replicating it and replacing it in some ways in some places. So in the same way that you had underground presses in the Polish solidarity movement, now you have Twitter and Facebook. Those are the things that are very good at giving a rolling account of what’s going on. Quite often I don’t really trust what I’m seeing on Twitter. So it’s difficult to get a balance. You really have to sit there with a lot of social media sources and look at all of them to get an overall sense of the picture. I think it is possible though.